Recall this from the first managerial accounting chapter: “Managerial accounting information is ultimately based on internal specifications for data accumulation and presentation. These internal specifications should be clear and consistent. Great care must be taken to insure that resulting reports are sufficiently logical to enable good decisions.” Previous chapters have introduced managerial accounting concepts, and provide a foundation to look more closely at some of the techniques for internal reporting. This chapter’s initial topic pertains to an internal reporting method for measuring and presenting inventory and income, known as variable costing.

Recall this from the first managerial accounting chapter: “Managerial accounting information is ultimately based on internal specifications for data accumulation and presentation. These internal specifications should be clear and consistent. Great care must be taken to insure that resulting reports are sufficiently logical to enable good decisions.” Previous chapters have introduced managerial accounting concepts, and provide a foundation to look more closely at some of the techniques for internal reporting. This chapter’s initial topic pertains to an internal reporting method for measuring and presenting inventory and income, known as variable costing.

Absorption Costing

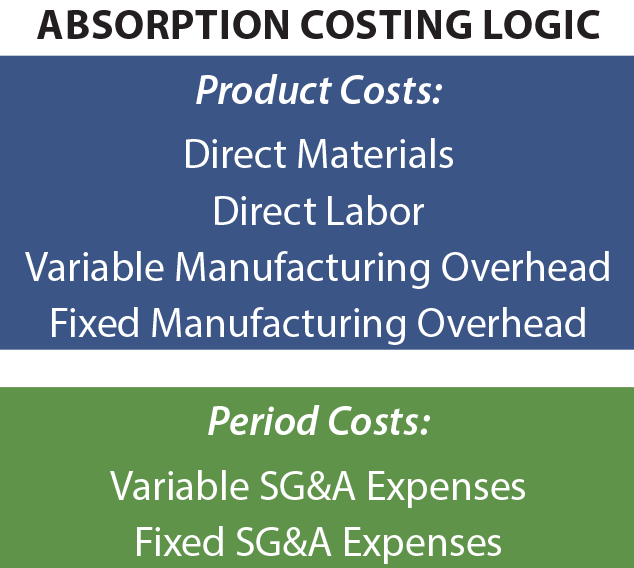

Generally accepted accounting principles require use of absorption costing (also known as “full costing”) for external reporting. Under absorption costing, normal manufacturing costs are considered product costs and included in inventory.

As sales occur, the cost of inventory is transferred to cost of goods sold, meaning that the gross profit is reduced by all costs of manufacturing, whether those costs relate to direct materials, direct labor, variable manufacturing overhead, or fixed manufacturing overhead. Selling, general, and administrative costs (SG&A) are classified as period expenses.

As sales occur, the cost of inventory is transferred to cost of goods sold, meaning that the gross profit is reduced by all costs of manufacturing, whether those costs relate to direct materials, direct labor, variable manufacturing overhead, or fixed manufacturing overhead. Selling, general, and administrative costs (SG&A) are classified as period expenses.

The rationale for absorption costing is that it causes a product to be measured and reported at its complete cost. Because costs like fixed manufacturing overhead are difficult to identify with a particular unit of output does not mean that they were not a cost of that output. As a result, such costs are allocated to products. However valid the claims are in support of absorption costing, the method does suffer from some deficiencies as it relates to enabling sound management decisions. Absorption costing information may not always provide the best signals about how to price a product, reach conclusions about discontinuing a product, and so forth.

Variable Costing

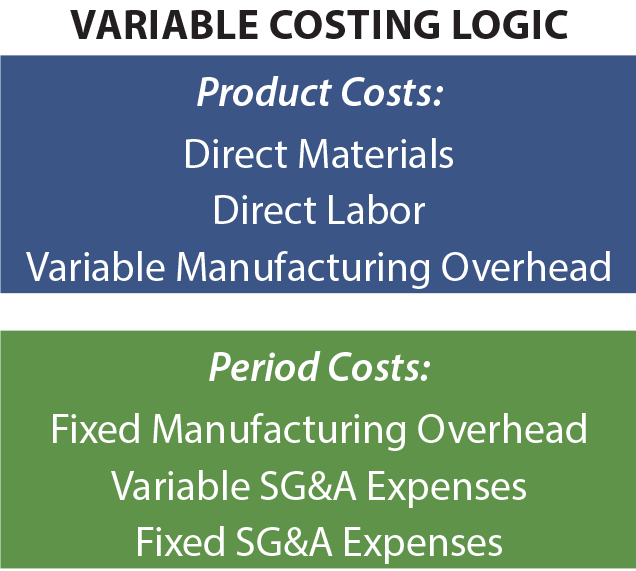

To allow for deficiencies in absorption costing data, strategic finance professionals will often generate supplemental data based on variable costing techniques. As its name suggests, only variable production costs are assigned to inventory and cost of goods sold. These costs generally consist of direct materials, direct labor, and variable manufacturing overhead. Fixed manufacturing costs are regarded as period expenses along with SG&A costs. In some ways, this understates the true cost of production. How then can it aid in decision making? The short answer is that the fixed manufacturing overhead is going to be incurred no matter how much is produced. In the long run, a business must recover those costs to survive. But, on a case-by-case basis, including fixed manufacturing overhead in a product cost analysis can result in some very wrong decisions.

To allow for deficiencies in absorption costing data, strategic finance professionals will often generate supplemental data based on variable costing techniques. As its name suggests, only variable production costs are assigned to inventory and cost of goods sold. These costs generally consist of direct materials, direct labor, and variable manufacturing overhead. Fixed manufacturing costs are regarded as period expenses along with SG&A costs. In some ways, this understates the true cost of production. How then can it aid in decision making? The short answer is that the fixed manufacturing overhead is going to be incurred no matter how much is produced. In the long run, a business must recover those costs to survive. But, on a case-by-case basis, including fixed manufacturing overhead in a product cost analysis can result in some very wrong decisions.

This last point can be made clear with a very simple illustration. Assume that a company produces 10,000 units of a product, and per unit costs are $2 for direct material, $3 for direct labor, and $4 for variable factory overhead. In addition, fixed factory overhead amounts to $10,000. The product cost under absorption costing is $10 per unit, consisting of the variable cost components ($2 + $3 + $4 = $9) and $1 of allocated fixed factory overhead ($10,000/10,000 units). Under variable costing, the product cost is limited to the variable production costs of $9. Now consider a “management decision.” Assume the company is approached to sell one additional unit at $9.50. This sale will not result in any added SG&A cost or otherwise impact sales of other units.

Based on absorption costing methods, the additional unit appears to produce a loss of $0.50, and it appears that the correct decision is to not make the sale. Variable costing suggests a profit of $0.50, and the information appears to support a decision to make the sale. Management may well decide to sell the additional unit at $9.50 and produce an additional $0.50 for the bottom line. Remember, no other costs will be generated by accepting this proposed transaction. If management was limited to absorption costing information, this opportunity would likely have been foregone.

Based on absorption costing methods, the additional unit appears to produce a loss of $0.50, and it appears that the correct decision is to not make the sale. Variable costing suggests a profit of $0.50, and the information appears to support a decision to make the sale. Management may well decide to sell the additional unit at $9.50 and produce an additional $0.50 for the bottom line. Remember, no other costs will be generated by accepting this proposed transaction. If management was limited to absorption costing information, this opportunity would likely have been foregone.

Variable Costing In Action

The preceding illustration highlights a common problem faced by many businesses. Consider the plight of a typical airline. As time nears for a scheduled departure, unsold seats represent lost revenue opportunities. The variable cost of adding one more passenger to an unfilled seat is quite negligible, and almost any amount of revenue that can be generated has a positive contribution to profit! An automobile manufacturer may have a contract with union labor requiring employees to be paid even when the production line is silent. As a result, the company may conclude that they are better off building cars at a “loss” to avoid an even “larger loss” that would result if production ceased. Professional sports clubs will occasionally offer deep discount tickets for unpopular games. Obviously, the variable cost of allowing someone to watch the game is nominal. Likely, variable costing information is taken into account in making the decisions relating to these types of examples. Each decision is intended to be in the best interest of the entity, even when a full costing approach causes the decision to look foolish.

The preceding illustration highlights a common problem faced by many businesses. Consider the plight of a typical airline. As time nears for a scheduled departure, unsold seats represent lost revenue opportunities. The variable cost of adding one more passenger to an unfilled seat is quite negligible, and almost any amount of revenue that can be generated has a positive contribution to profit! An automobile manufacturer may have a contract with union labor requiring employees to be paid even when the production line is silent. As a result, the company may conclude that they are better off building cars at a “loss” to avoid an even “larger loss” that would result if production ceased. Professional sports clubs will occasionally offer deep discount tickets for unpopular games. Obviously, the variable cost of allowing someone to watch the game is nominal. Likely, variable costing information is taken into account in making the decisions relating to these types of examples. Each decision is intended to be in the best interest of the entity, even when a full costing approach causes the decision to look foolish.

Double-Edged Sword

A typical illustration of decision making based on variable costing data looks simple enough. But, such decisions are actually very tricky. Considerable business savvy is necessary, and there are several traps that must be avoided. First, a business must ultimately recover the fixed factory overhead and all other business costs; the total units sold must provide enough margin to accomplish this purpose. It would be easy to use up full manufacturing capacity, one sale at a time, and not build in enough margin to take care of all the other costs. If every transaction were priced to cover only variable cost, the entity would quickly go broke. Second, if a company offers special deals on a selective basis, regular customers may become alienated or hold out for lower prices. The key point here is that variable costing information is useful, but it should not be the sole basis for decision making.

Avoiding A Downward Spiral

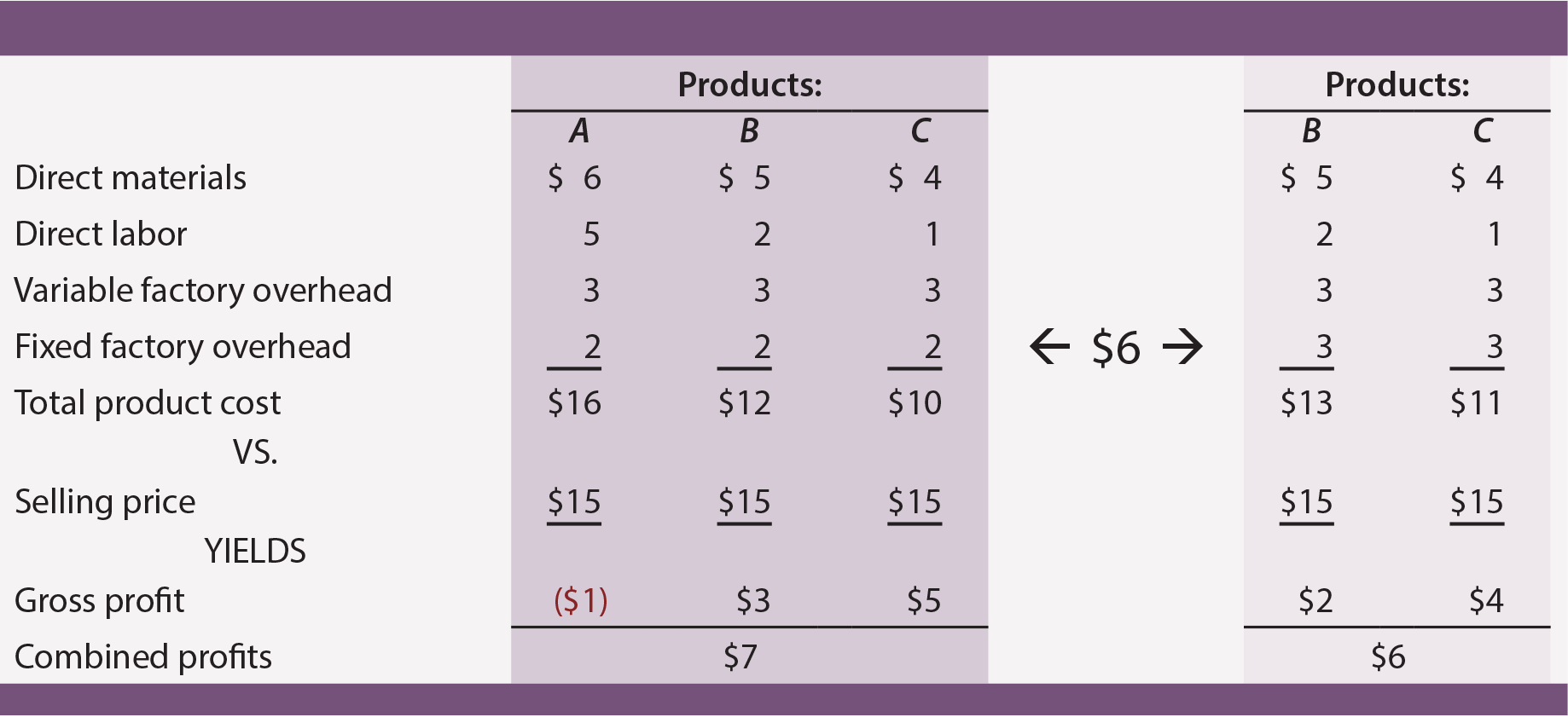

Variable costing data are quite useful in avoiding incorrect decisions about product discontinuation. Many businesses offer multiple products. Some will usually be more successful than others, and a logical business decision may be to focus on the best-performing units, while discontinuing others. Assume that a company offers products A, B, and C. Each is being produced in equal proportion, and the company is fully able to meet customer demand from existing capacity (i.e., producing more will not increase sales). The company is not incurring any variable costs relating to selling, general, and administration efforts.

From the absorption costing data in the dark shaded area, it appears that Product A is yielding a negative gross profit. Logically, a manager may target that product for discontinuation. However, if that decision is reached, Products B and C will each have to absorb more fixed factory overhead. The revised cost data (in the light shaded area) show that eliminating Product A will actually reduce overall profitability!

The decline in overall profits from discontinuing the “loser” occurs because the “loser” was absorbing some fixed cost of production. The $15 selling price for Product A at least covered its variable cost ($6 + $5 + $3 = $14) and contributed toward coverage of the business’s unavoidable fixed cost burden. The lesson here is that a company must be very careful in eliminating “unprofitable” products. This decision can often result in a series of successive shifts in overhead to other remaining products. This, in turn, can cause other products to also appear unsuccessful.

A downward spiral of product discontinuation decisions can ultimately destroy a business that was otherwise successful. This illustration underscores why a good manager will not rely exclusively on absorption costing data. Variable costing techniques that help identify product contribution margins (as more fully described in the following paragraphs) are essential to guiding the decision process.

Confused? On the one hand, variable costing has been praised for its benefits in aiding decisions. On the other hand, it was noted that variable costing should not be used as the sole basis for making decisions.

Confused? On the one hand, variable costing has been praised for its benefits in aiding decisions. On the other hand, it was noted that variable costing should not be used as the sole basis for making decisions.

Variable costing is not a panacea, and guiding a business is not easy. Decision making is not as simple as applying a single mathematical algorithm to a single set of accounting data. A good manager must consider business problems from multiple perspectives. In the context of measuring inventory and income, a manager will want to understand both absorption costing and variable costing techniques. This information must be interlaced with knowledge of markets, customer behavior, and the like. The resulting conclusions can set in motion plans of action that bear directly on the overall fate of the organization.

Income Statement

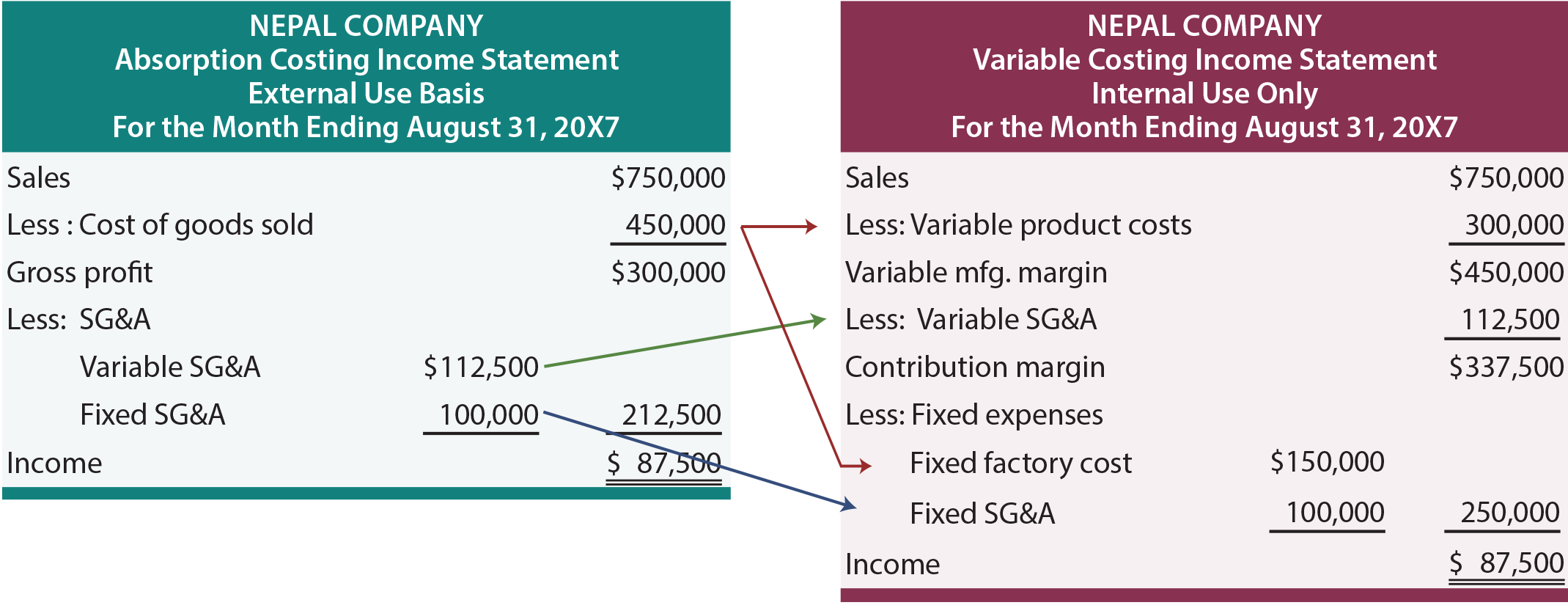

Much of the preceding discussion focused on per-unit cost assessments. In addition, the examples assumed that selling, general, and administrative costs were not impacted by specific actions. It is now time to consider aggregated financial data and take into account shifting amounts of SG&A. The following income statements present information about Nepal Company. On the left is the income statement prepared using the absorption costing method, and on the right is the same information using variable costing. For now, assume that Nepal sells all that it produces, resulting in no beginning or ending inventory.

With absorption costing, gross profit is derived by subtracting cost of goods sold from sales. Cost of goods sold includes direct materials, direct labor, and variable and allocated fixed manufacturing overhead. From gross profit, variable and fixed selling, general, and administrative costs are subtracted to arrive at net income. This approach should look familiar. It is the presentation that is typical of financial statements generated for general use by shareholders and other persons external to the daily operations of a business.

With variable costing, all variable costs are subtracted from sales to arrive at the contribution margin. Nepal’s presentation divides variable costs into two categories. The variable product costs include all variable manufacturing costs (direct materials, direct labor, and variable manufacturing overhead). These costs are subtracted from sales to produce the variable manufacturing margin. Some of Nepal’s SG&A costs also vary with sales. As a result, these amounts must also be subtracted to arrive at the true contribution margin. Management must take into account all variable costs (whether related to manufacturing or SG&A) in making critical decisions. For instance, Nepal may pay sales commissions that are based on sales; to exclude those from consideration in evaluating the “margin” that is to be generated from a particular transaction or event would be quite incorrect. From the contribution margin are subtracted both fixed factory overhead and fixed SG&A costs.

Because Nepal does not carry inventory, the income is the same under absorption and variable costing. The difference is only in the manner of presentation. Carefully study the arrows that show how amounts appearing in the absorption costing approach would be repositioned in the variable costing income statement. Since the bottom line is the same under each approach, this may seem like much to do about nothing. But, remember that “gross profit” is not the same thing as “contribution margin,” and decision logic is often driven by consideration of contribution effects. Further, when inventory levels fluctuate, the periodic income will differ between the two methods.

Impact Of Inventory

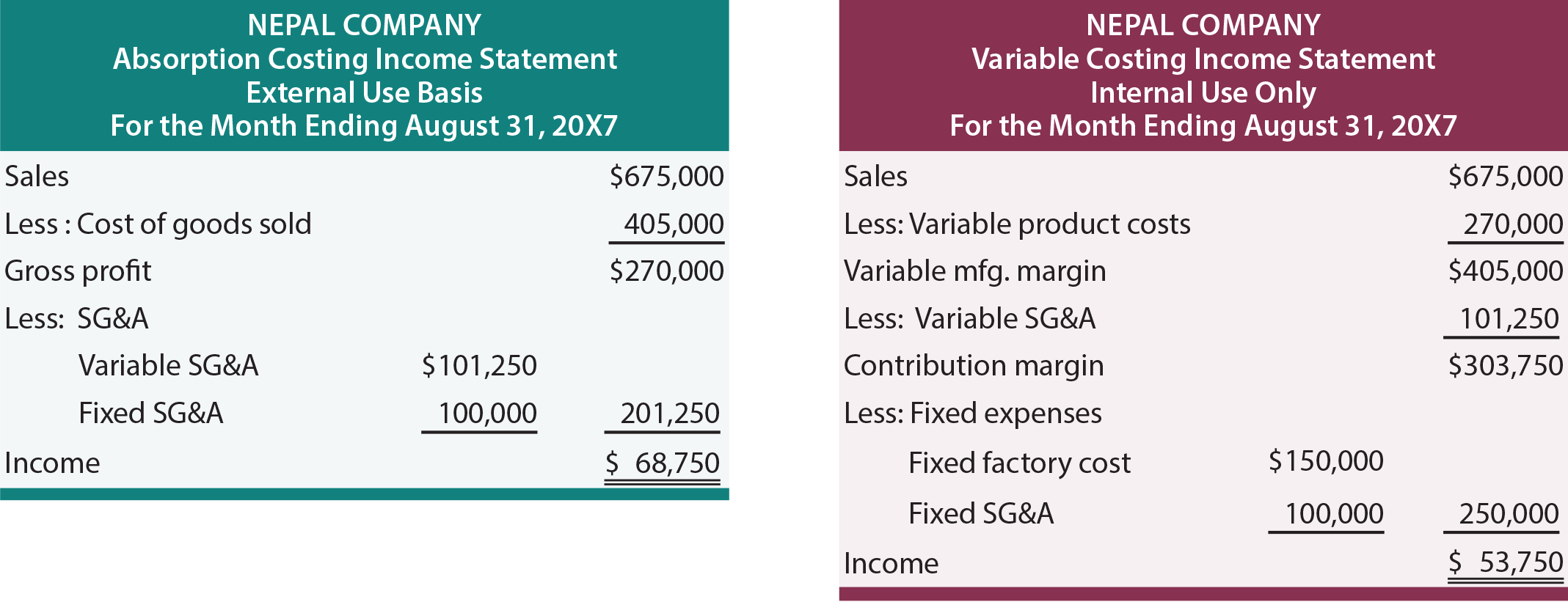

The following income statements are identical to those previously illustrated, except sales and variable expenses are reduced by 10%. Assume that the units relating to the “10% reduction” were nevertheless manufactured. What is the effect of this inventory build-up? Income is higher under absorption costing by $15,000. This is consistent with a general rule of thumb: Increases in inventory cause income to be higher under absorption costing than under variable costing, and vice versa.

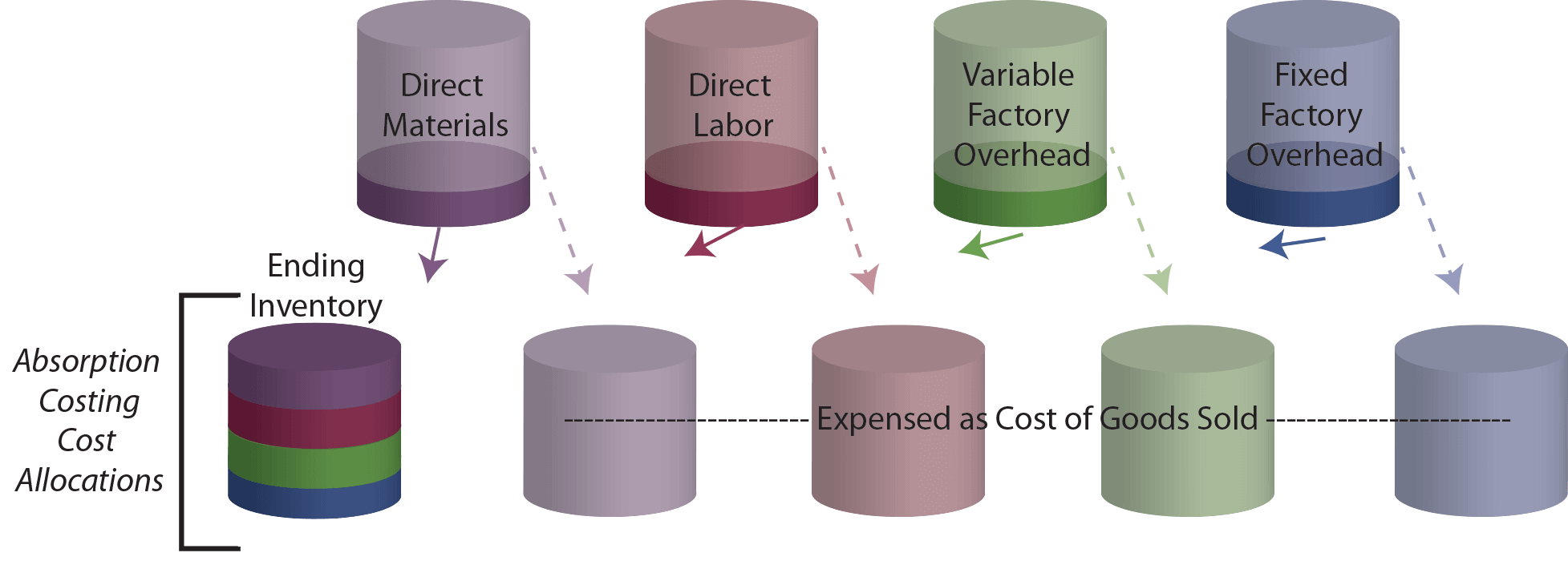

To further examine the reason income is higher, remember that $450,000 was attributed to total production under absorption costing. Of this amount, 10% ($45,000) is now diverted into inventory. Under variable costing, total product costs were $300,000 and 10% ($30,000) of that amount would be assigned to inventory. As a result, $15,000 more is assigned to inventory under absorption costing. This logically coincides with the degree to which income is higher! Another way to view the impact of the inventory build-up is to examine the following “cups.” The top set of cups initially contains the costs incurred in the manufacturing process. With absorption costing, those cups must be emptied into either cost of goods sold or ending inventory.

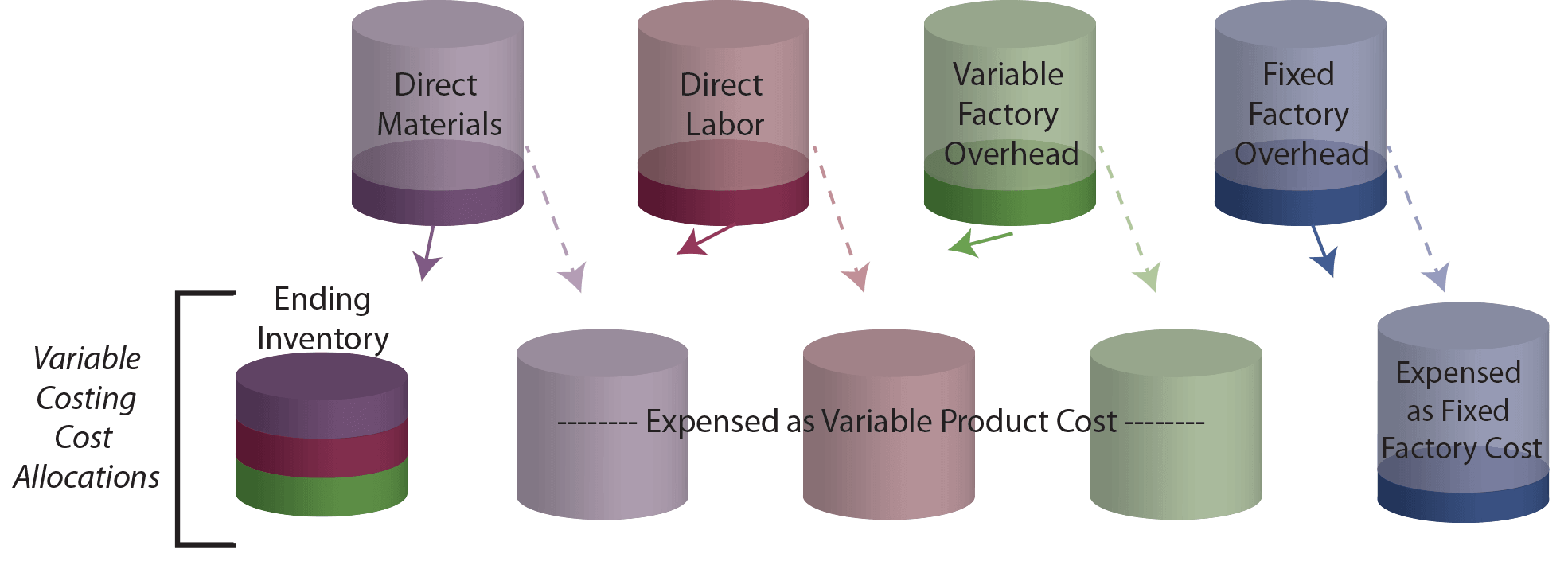

Compare the drawing above to the variable costing illustration that follows. The ending inventory cup contains less with variable costing because there is no fixed factory overhead in ending inventory!

Recognize that a reduction in inventory during a period will cause the opposite effect from that shown. Specifically, a portion of the contents of the beginning inventory cup would be transferred to expense commensurate with the decrease in inventory. Since the inventory cup contains less under variable costing, expect expenses to be lower and income to be higher.

| Did you learn? |

|---|

| Understand absorption (full) costing logic, and know that it is required by GAAP. |

| Understand variable costing logic, and know how it is beneficial in the management decision process. |

| Be able to prepare an absorption costing income statement. |

| Be able to prepare a variable costing income statement. |

| Be able to demonstrate how inventory fluctuations cause income to differ under absorption vs. variable costing. |