Chapter 17 introduced product costing, the schedule of cost of goods manufactured, and the basic cost flow of a manufacturer. In that preliminary presentation, most cost data (e.g., ending work in process inventory, etc.) were “given.” Chapter 18 showed how cost data are used in making important business decisions. How does one determine the cost data for products and services that are the end result of productive processes? The answer to this question is complex.

Chapter 17 introduced product costing, the schedule of cost of goods manufactured, and the basic cost flow of a manufacturer. In that preliminary presentation, most cost data (e.g., ending work in process inventory, etc.) were “given.” Chapter 18 showed how cost data are used in making important business decisions. How does one determine the cost data for products and services that are the end result of productive processes? The answer to this question is complex.

Multiple persons, parts, and processes may be needed to bring about a deliverable output. Think about an automobile manufacturer; what is the dollar amount of “cost” for the hundreds of cars that are in various stages of completion at the end of a month? This chapter, and the next, will provide a sense of how business information systems are used to generate these important cost data. This chapter focuses on the job costing technique, and the next chapter will look more closely at process costing and other options.

Basic Job Costing

Job costing (also called job order costing) is best suited to those situations where goods and services are produced upon receipt of a customer order, according to customer specifications, or in separate batches. For example, a ship builder would likely accumulate costs for each ship produced. An aircraft manufacturer would find this method logical. Construction companies and home builders would naturally gravitate to a job costing approach. Each job is somewhat unique. Materials and labor can be readily traced to each job, and the cost assignment logically follows.

Job Costing Example

Jack Castle owns an electrical contracting company, Castle Electric. Jack provides a variety of products and services to clientele. Jack has four employees, a rented shop, a broad inventory of parts, and a fleet of five service trucks. On a typical day, Jack will arrive at the shop early and line out the day’s work assignments. Around 8:00 a.m., his electricians arrive, and he gives them their assignments, as well as the necessary parts and equipment they will need. They are then dispatched to the various job sites.

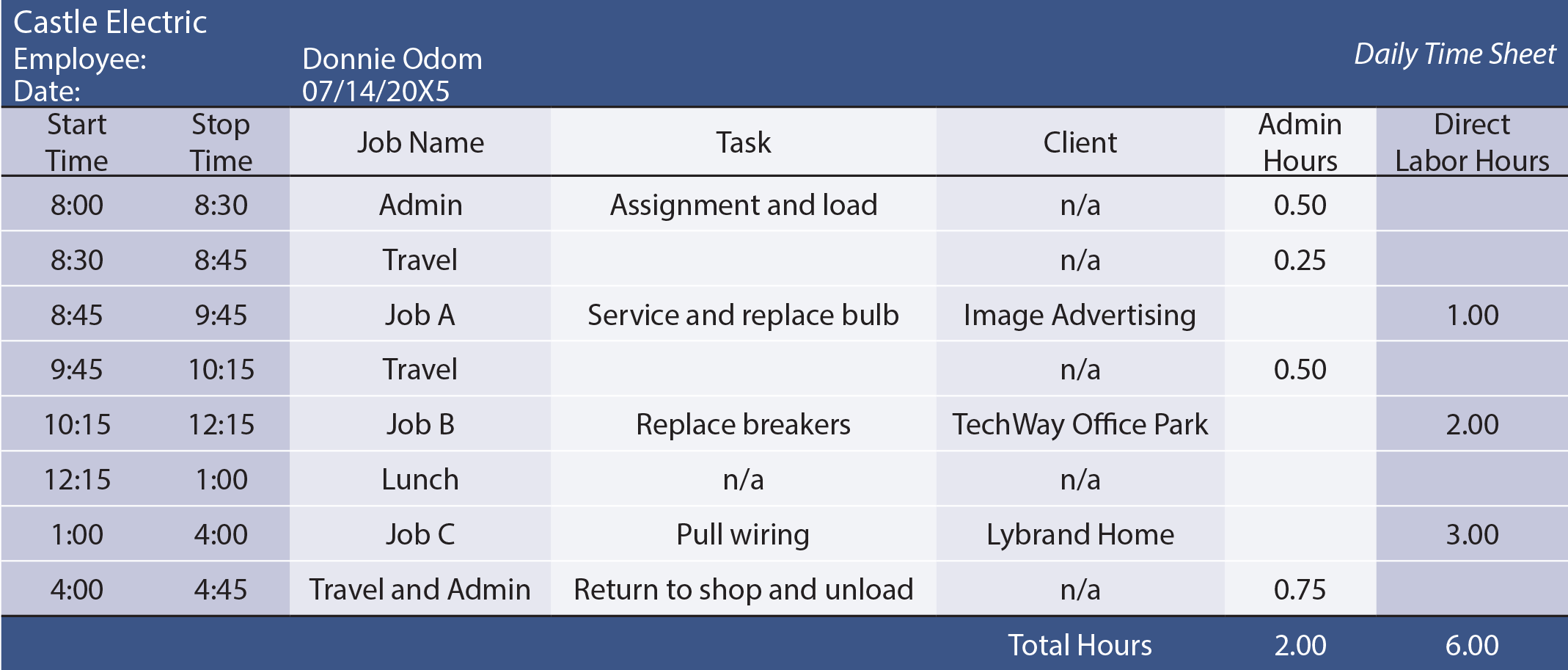

One of Jack’s electricians is Donnie Odom. On July 14, Donnie arrived at the shop at 8:00 a.m. He first spent 30 minutes getting his assignments and loading a service truck with necessary items to complete the day’s work. His three tasks for the day included:

- Job A: Cleaning and reconnecting the electrical connections and replacing a flood light atop a billboard (materials required include one lamp at $150).

- Job B: Replacing the breakers on an old electrical distribution panel at an office building (materials required include 20 breakers at $20 each).

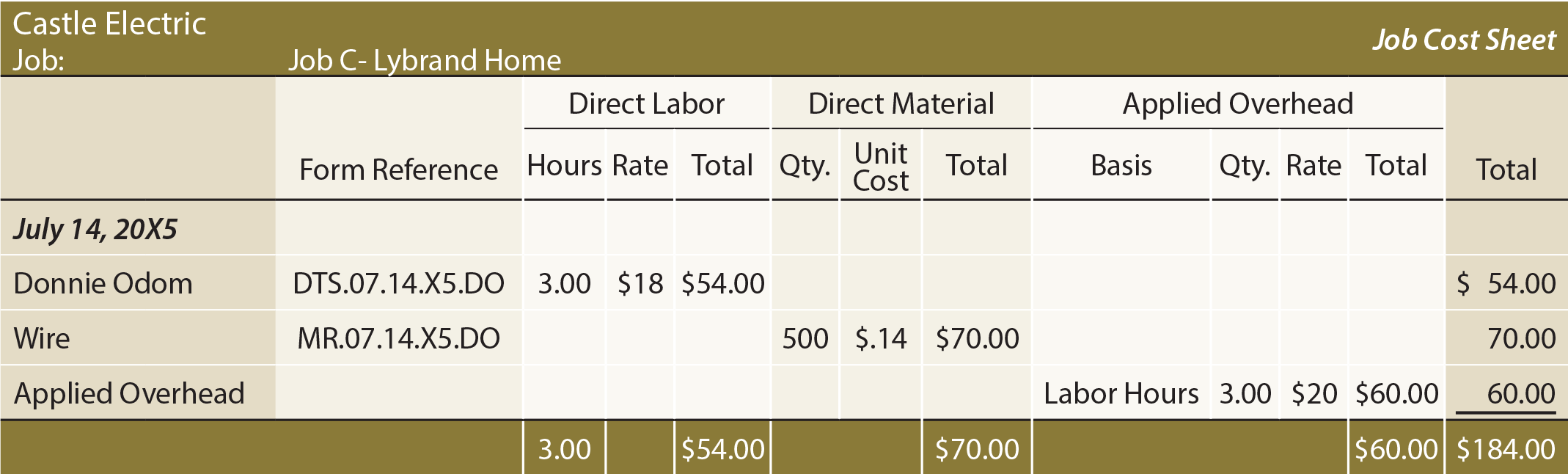

- Job C: Pulling wire for a new residence under construction (materials required include 500 feet of wire at $0.14 per foot).

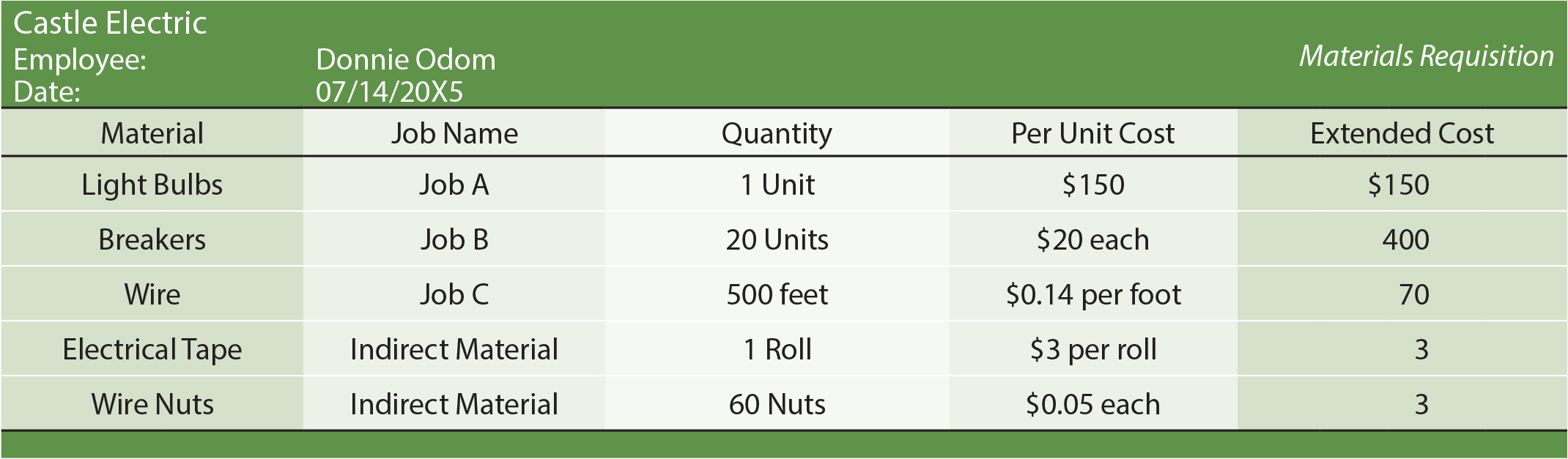

Donnie successfully completed all three tasks. He spent one hour on the billboard, two hours on the electrical panel, and three hours on the residential installation. The other two hours of his 8-hour day were spent on indirect job administration and travel. During the day, Donnie also used a roll of electrical tape ($3) and a box of wire nuts (60 nuts at $0.05 each). Donnie is paid $18 per hour. Donnie drove a truck and he used a variety of tools, ladders, and other specialized equipment. Jack is paid $25 per hour, and he does not work on any specific job. Instead, his time is spent doing inspections, getting permits, managing inventory, and other tasks.

How much did it “cost” to change the light on the billboard? Obviously, the job cost included the direct costs of the job; specifically, Donnie’s direct labor time (one hour) and the direct material (one lamp at $150). But, the job could not have gotten done without the shop, equipment, trucks, indirect labor time, tape, wire nuts, and so forth. These latter items constitute the indirect costs, or overhead. How are these costs assigned to a specific job?

Tracking Labor

A logical starting point is to specifically track labor cost. Donnie, and the other electricians, fill out a time report documenting time spent on each job, as well as the time spent on other tasks:

Tracking Material

Jack keeps detailed records of the material released to each job. When Donnie gathered up the light bulbs, breakers, wire, tape, and wire nuts on the morning of the 14th, some system needed to be in place to “check out” this material. The document that is used for this process is called a “materials request” or materials requisition form. This form will show what material is leaving the available raw materials stock and being put into production. Sometimes a separate form is prepared for each item, and sometimes a running list similar to the following is used:

This form provides essential documentation to track inventory. It also reveals that the “direct material” for the billboard task (Job A) was $150 (the light bulb). The wire nuts and tape that might have been used on the billboard will be dealt with as overhead, which is discussed later.

Although the illustrated form lists the material cost, that will not always be the case. Sometimes, a business will not be particularly interested in letting employees see cost information, or cost information may not be readily available. In either case, the form will instead include a part or serial number. A subsequent clerical task will be to identify the cost of the particular parts that were put into production.

Tracking Overhead

Jack would have a huge task at hand if he tried to daily trace all items of overhead. For instance:

- How hard would it be to track the “indirect material”? How many wire nuts were used on the billboard? How many inches of electrical tape were used? What was the cost of these items?

- What about indirect labor? Should the cost of Donnie’s two hours of travel and administrative time be spread over the three jobs equally, pro-rata based on hours, or on some other basis? What about Jack’s time? He is supervising four electricians. Should the cost of his time be allocated 1/4 to each, or based on some other formula?

- One must also consider the cost of rent, trucks, and so forth. Donnie needed a ladder to scale the billboard. How much is the “ladder cost” for one job?

Tracking overhead is tricky. One way this is done is by using a predetermined overhead rate. Assume Jack sat down at the beginning of the year with his accountant. Together they carefully considered all of the production overhead that was anticipated during the year. This included the cost of Jack’s time, rent, the cost of vehicles, insurance, taxes, utilities, indirect labor, indirect materials, depreciation of long-lived assets, and so forth.

The expected total came to about $150,000. Jack figures that his four electricians will work a total of about 7,500 direct labor hours during the year. By comparing these two numbers ($150,000 and 7,500 hours), it is now possible to “model” that overhead is $20 per direct labor hour. A logical overhead application rate is thus determined.

Two things should be made clear. First, overhead application is arbitrary. Jack decided to apply overhead based on direct labor hours; this is a common choice, but not the only choice. Some other systematic and rational approach could have been developed. Ordinarily, one would try to establish some correlation between the application base and overall cost incurrence. For instance, feet of wire used (instead of direct labor hours) could have been selected as the application base. But, feet of wire used would be hard to defend since two of Donnie’s three jobs did not use any wire and would not be assigned any of the business overhead.

Two things should be made clear. First, overhead application is arbitrary. Jack decided to apply overhead based on direct labor hours; this is a common choice, but not the only choice. Some other systematic and rational approach could have been developed. Ordinarily, one would try to establish some correlation between the application base and overall cost incurrence. For instance, feet of wire used (instead of direct labor hours) could have been selected as the application base. But, feet of wire used would be hard to defend since two of Donnie’s three jobs did not use any wire and would not be assigned any of the business overhead.

The point is that some logical method needs to be used to attach overhead costs to output, but no single choice is absolute. Cost allocation necessarily involves some degree of arbitrary methodology; this is neither bad nor good, it is just reality. In some ways, costing is more of an “art” than “science,” despite its outward appearance of mathematical precision.

Second, expect differences between the actual overhead and the amount applied to production. For instance, Jack will likely discover that actual overhead is more or less than $150,000. Jack will also find that his electricians will probably work more or less than the anticipated 7,500 hours. Accounting for the difference between the amount of overhead applied to production (i.e., direct labor hours X $20 per hour rate) and the actual amount spent will be shown later in the chapter.

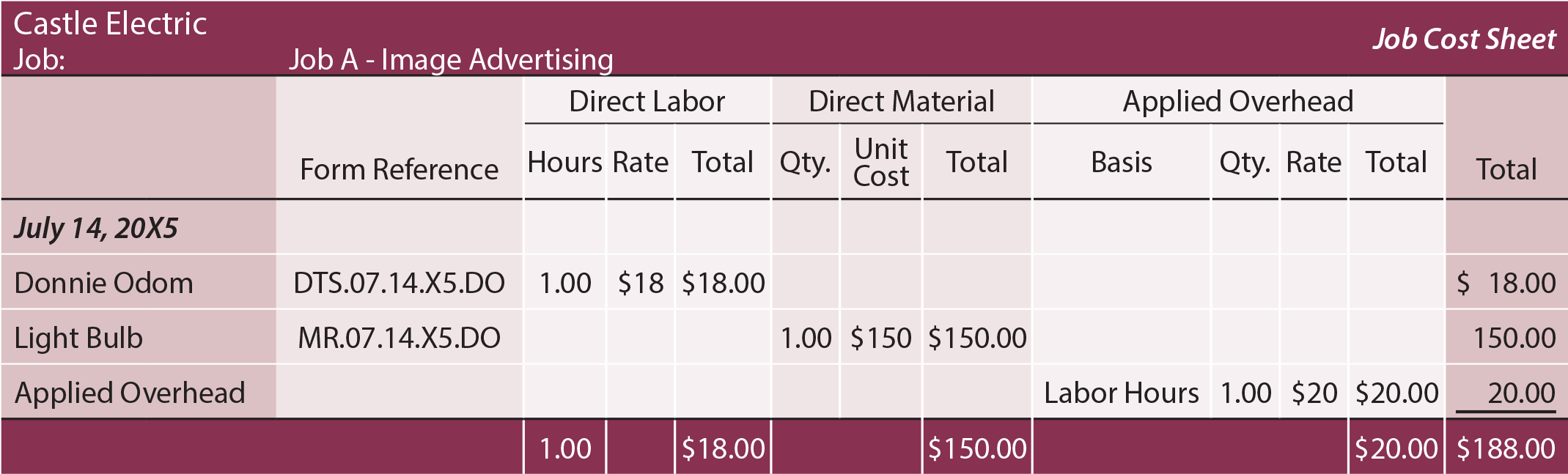

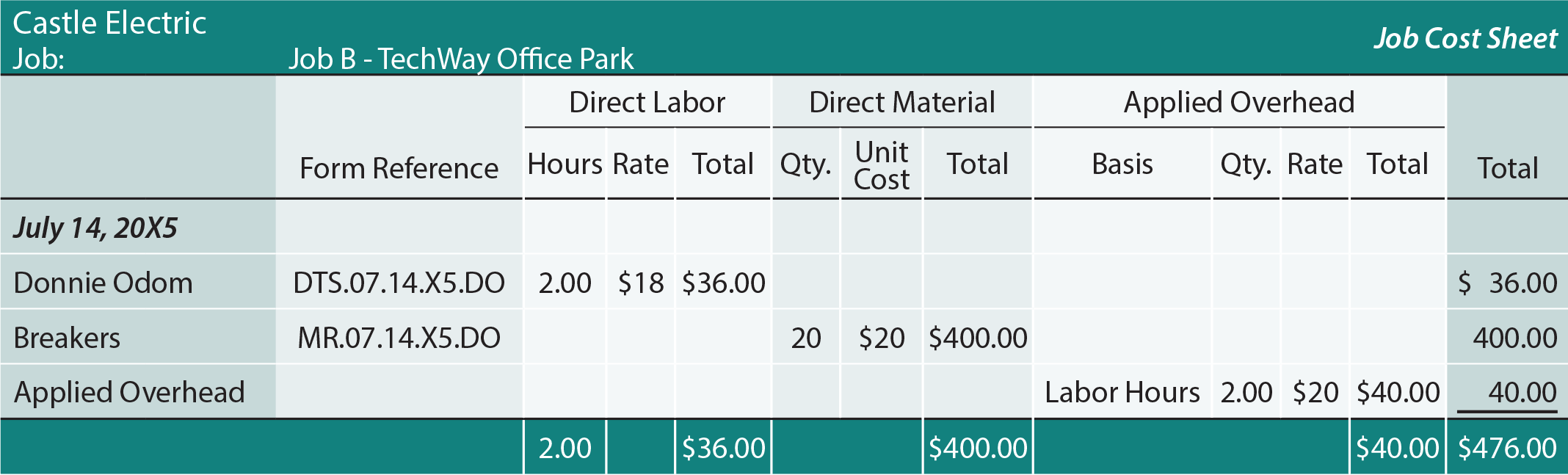

Job Cost Sheet

The information on the daily time sheet and materials requisition form can be logically transferred to appropriate job cost sheets:

Note the form reference to the source documents (e.g., “DTS.07.14.X5.DO” to indicate “daily time sheet of July 14, 20X5, for Donnie Odom”). In similar fashion, Donnie’s materials requisition form was used as the source document for compiling the direct material information for each job. Overhead was applied directly to the job cost sheets based upon the predetermined overhead application scheme of $20 per direct labor hour.

Database System

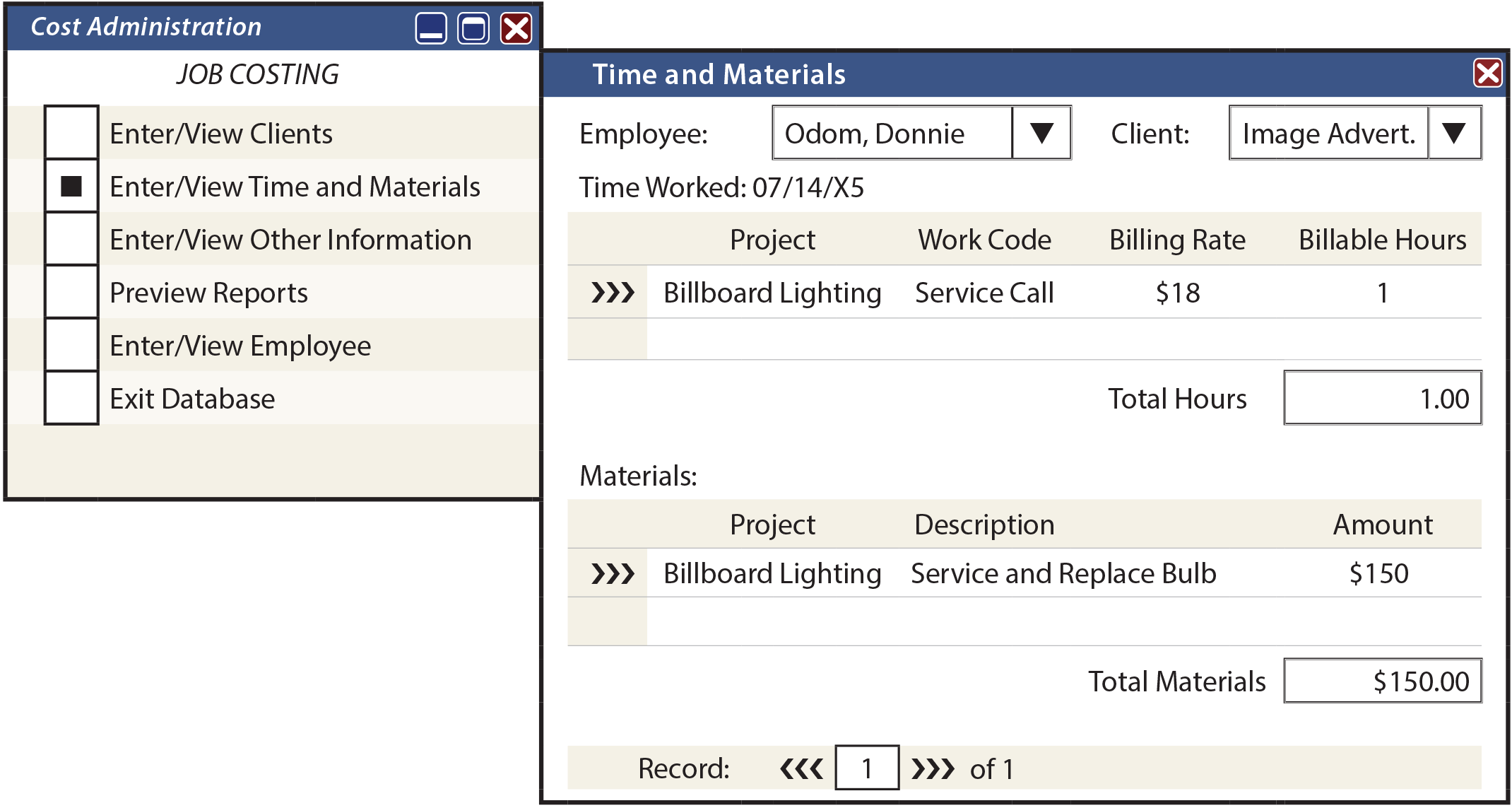

Jack could maintain some or all of his job costing system manually. Or, he could use an electronic spreadsheet to prepare reports similar to those just illustrated. However, the electronic database is a more powerful tool. A number of commercial packages are available.

Generalizing, data are entered via a user-friendly input form that includes a number of predetermined “slots” for entering desired information. For instance, below is a data entry form for entering Donnie’s time and material for the 14th:

The benefit of the database approach is that information is only entered once; it need not be transferred to other forms. The computer files can be queried in many ways and generate more than a simple job cost report.

For instance, Jack could use the customized reports feature to find all jobs on which billboard light bulbs were used during the past 18 months, or determine the total direct labor hours of any employee for a selected time interval, or identify all jobs performed for a selected client, and so forth. Such databases provide a powerful management tool.

Example For Larger Job

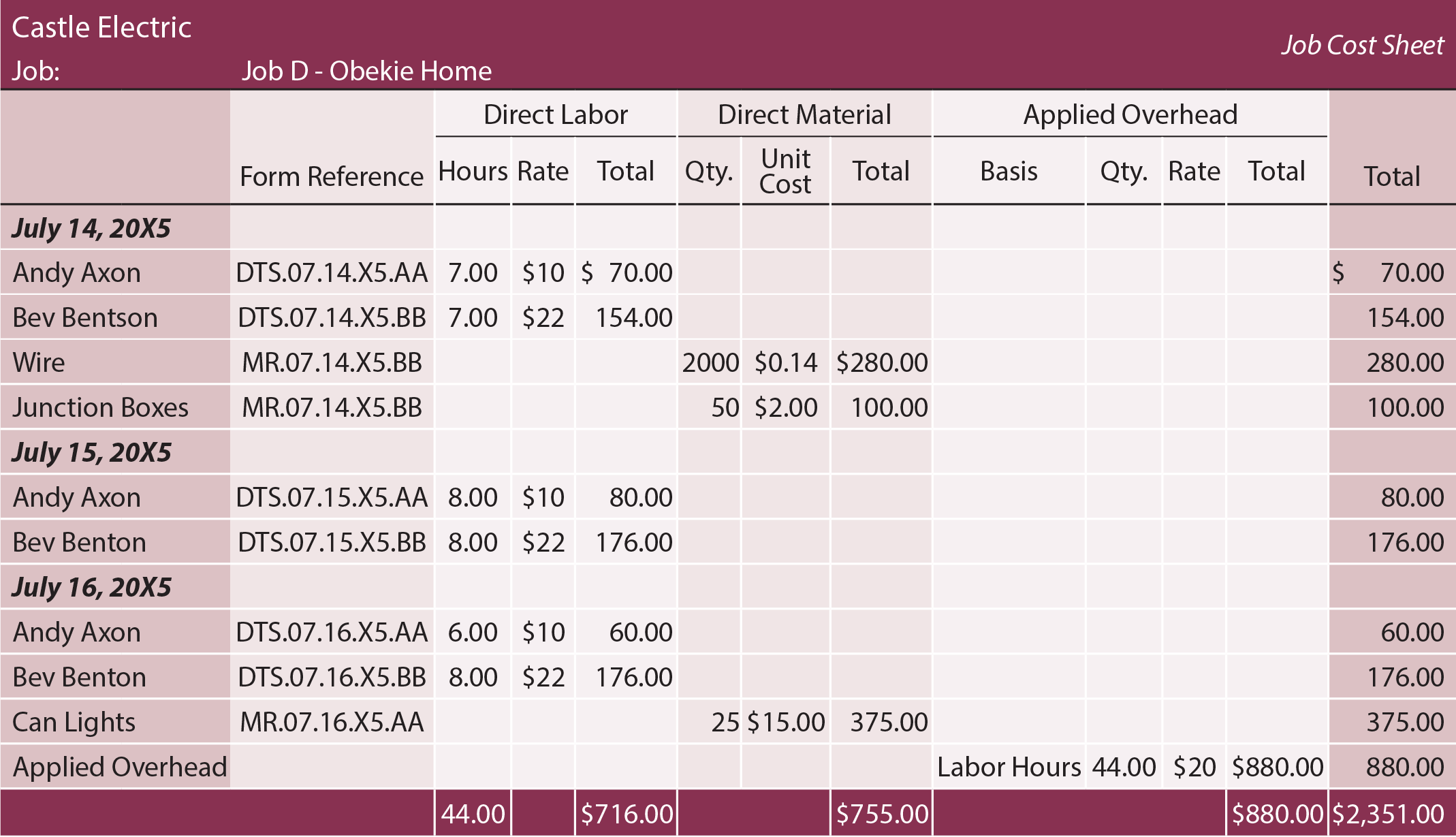

Thus far, the illustration has focused only on Donnie’s activities. He had relatively simple assignments on July 14 and was able to complete three separate jobs by himself. But, remember that Jack has three other electricians and many other jobs. Some of these jobs may require multiple employees and extend over several days. One such job was the new home of Aba Obekie. This job took two electricians (Andy Axon and Bev Bentson) three full days to complete. The resulting job cost sheet appeared as follows:

Moving Beyond Basic Concepts

Thus far, a basic illustration has been used. What this fails to consider are factors such as these:

- The sophistication of the information systems that are used to track job costs.

- The debits and credits that are needed to track the accumulation and application of costs within a company’s general ledger system.

- The ultimate disposition of the difference between applied and actual overhead.

Each of these issues will be dealt with in following sections of this chapter.

| Did you learn? |

|---|

| Describe the approach to accumulating product cost using a job costing system. |

| Develop an illustration that portrays the typical content of a job cost sheet. |

| Identify the purpose of a materials requisition. |

| How is an overhead application rate calculated, and how is it applied? |

| What is a database system, and how does it facilitate job costing mechanics? |