A sign hanging on the wall of a business establishment said: ”Managers are Paid to Manage — If There Were No Problems We Wouldn’t Need Managers.” This suggests that all organizations have problems, and it is management’s responsibility to deal with them. While there is some truth to this characterization, it is perhaps more reflective of a “not so impressive” organization that is moving from one crisis to another. Managerial talent goes beyond just dealing with the problems at hand.

A sign hanging on the wall of a business establishment said: ”Managers are Paid to Manage — If There Were No Problems We Wouldn’t Need Managers.” This suggests that all organizations have problems, and it is management’s responsibility to deal with them. While there is some truth to this characterization, it is perhaps more reflective of a “not so impressive” organization that is moving from one crisis to another. Managerial talent goes beyond just dealing with the problems at hand.

What does it mean to manage? Managing requires numerous skill sets. Among those skills are vision, leadership, and the ability to procure and mobilize financial and human resources. All of these tasks must be executed with an understanding of how actions influence human behavior within, and external to, the organization. Furthermore, good managers must have endurance to tolerate challenges and setbacks while trying to forge ahead. To successfully manage an operation also requires follow through and execution. Because each management action is predicated upon some specific decision, good decision making is crucial to being a successful manager.

Decision Making

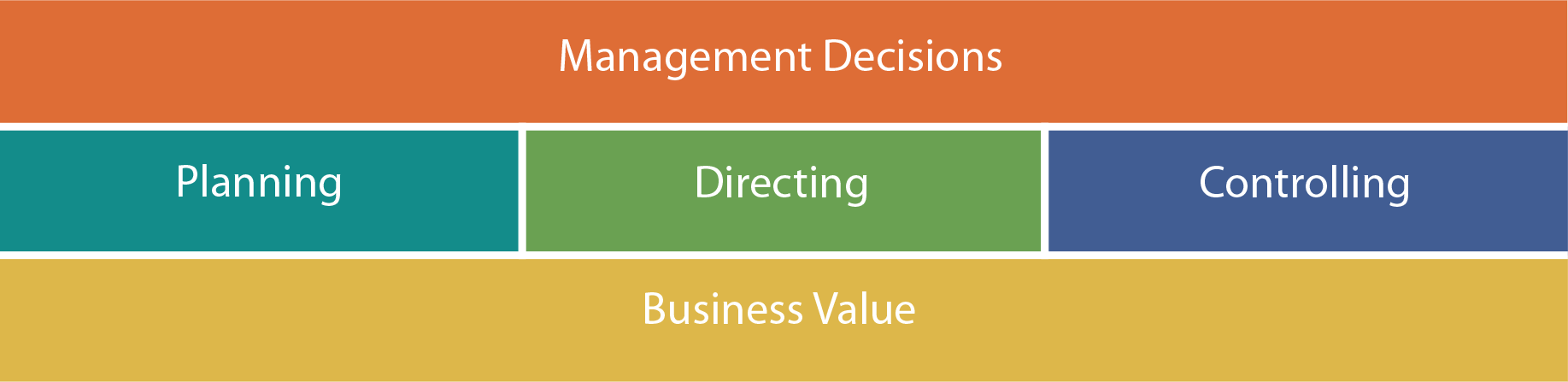

Good decision making is rarely done by intuition. Consistently good decisions result from diligent accumulation and evaluation of information. Managerial accounting provides the information needed to fuel the decision-making process. Managerial decisions can be categorized according to three interrelated business processes: planning, directing, and controlling. Correct execution of each of these activities culminates in the creation of business value. Conversely, failure to plan, direct, or control is a road map to failure. The central theme is this: (1) business value results from good decisions, (2) decisions must occur across a spectrum of planning, directing, and controlling activities, and (3) quality decision making can only consistently occur by reliance on information.

Planning

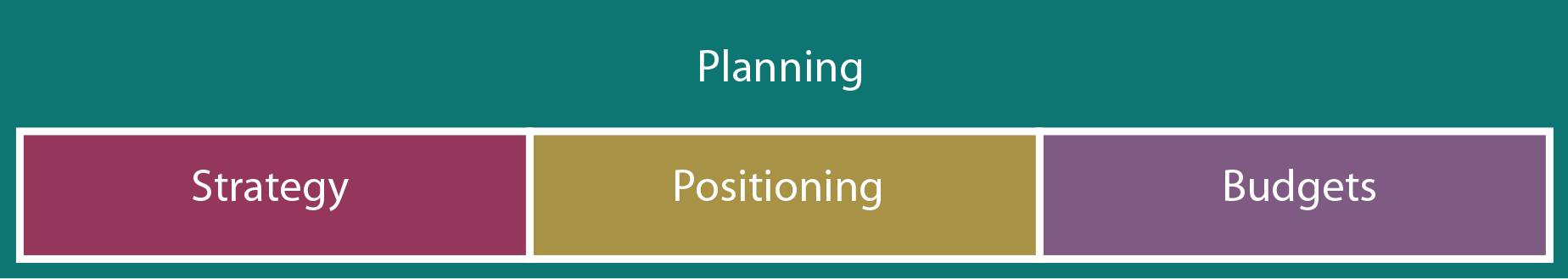

A business must plan for success. What does it mean to plan? It is about deciding on a course of action to reach a desired outcome. Planning must occur at all levels. First, it occurs at the high level of setting strategy. It then moves to broad-based thought about how to establish an optimum “position” to maximize the potential for realization of goals. Finally, planning must give thoughtful consideration to financial realities/constraints and anticipated monetary outcomes (budgets).

A business organization may be made up of many individuals. These individuals must be orchestrated to work together in harmony. It is important that they share and understand the organizational plans. In short, “everyone needs to be on the same page.” As such, clear communication is imperative.

Strategy

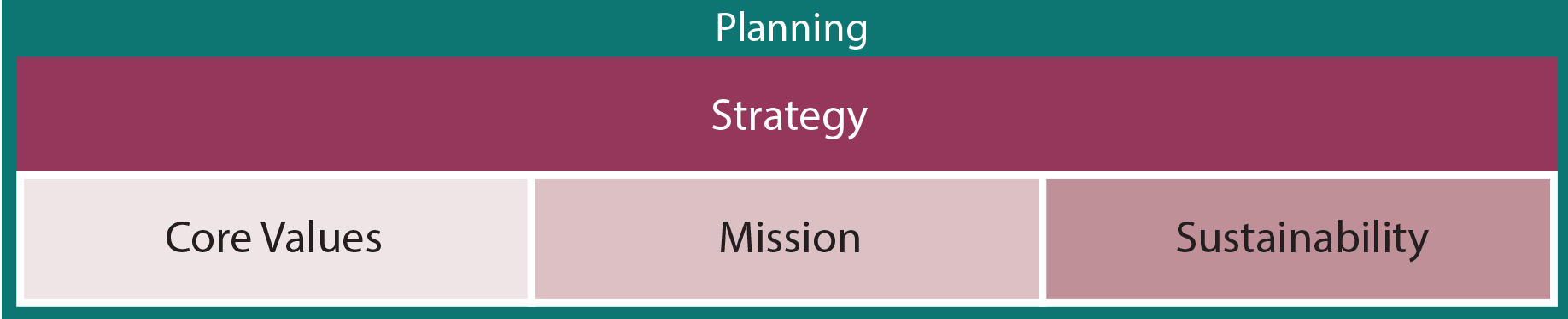

A business should invest considerable time and effort in developing strategy. Employees, harried with day-to-day tasks, sometimes fail to see the need to take on strategic planning. It is difficult to see the linkage between strategic endeavors and the day-to-day corporate activities associated with delivering goods and services to customers. But, strategic planning ultimately defines the organization. Specific strategy setting can take many forms, but generally includes elements pertaining to the definition of core values, mission, objectives, and sustainability.

Core Values — An entity should clearly consider and define the rules by which it will play. Core values can cover a broad spectrum involving concepts of fair play, human dignity, ethics, employment/promotion/compensation, quality, customer service, environmental awareness, and so forth. If an organization does not cause its members to understand and focus on these important elements, it will soon find participants becoming solely “profit-centric.” This behavior leads to a short-term focus and potentially dangerous practices that may provide the seeds of self-destruction. Remember that management is to build business value by making the right decisions, and decisions about core values are essential.

The globally-based Chartered Institute of Management Accountants (CIMA) joined with the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) to establish the Chartered Global Management Accountant (CGMA) designation in 2012. The CGMA designation distinguishes professionals who have advanced proficiency in finance, operations, strategy and management. The Institute of Management Accountants (IMA) is another representative group for the managerial accounting profession. IMA‘s overarching ethical principles include: Honesty, Fairness, Objectivity, and Responsibility. Many IMA members have earned the Certified Management Accountant (CMA) and Certified Financial Manager (CFM) designations. These certificates represent significant competencies in managerial accounting and financial management skills, as well as a pledge to follow the ethical precepts of the IMA.

Mission — Many companies attempt to prepare a pithy statement about their mission. For example:

Such mission statements provide a snapshot of the organization and provide a focal point against which to match ideas and actions. They provide an important planning element because they define the organization’s purpose and direction. Interestingly, some organizations have avoided “missioning,” in fear that it will limit opportunity for expansive thinking. For example, General Electric specifically states that it does not have a mission statement, per se. Instead, its operating philosophy and business objectives are clearly articulated each year in the Letter to Shareowners, Employees and Customers. In some sense, though, GE’s tag line reflects its mission: “imagination at work.” Perhaps the subliminal mission is to pursue opportunity wherever it can be found. As a result, GE is one of the world’s most diversified entities in terms of the range of products and services it offers.

Such mission statements provide a snapshot of the organization and provide a focal point against which to match ideas and actions. They provide an important planning element because they define the organization’s purpose and direction. Interestingly, some organizations have avoided “missioning,” in fear that it will limit opportunity for expansive thinking. For example, General Electric specifically states that it does not have a mission statement, per se. Instead, its operating philosophy and business objectives are clearly articulated each year in the Letter to Shareowners, Employees and Customers. In some sense, though, GE’s tag line reflects its mission: “imagination at work.” Perhaps the subliminal mission is to pursue opportunity wherever it can be found. As a result, GE is one of the world’s most diversified entities in terms of the range of products and services it offers.

Overall, the strategic structure of an organization is established by how well it defines its values and purpose. But, how does the managerial accountant help in this process? At first glance, these strategic issues seem to be broad and without accounting context. But, information is needed about the “returns” that are being generated for investors; this accounting information is necessary to determine whether the profit objective is being achieved. Actually, though, managerial accounting goes much deeper.

For example, how are core values policed? Consider that someone must monitor and provide information on environmental compliance. What is the most effective method for handling and properly disposing of hazardous waste? Are there alternative products that may cost more to acquire but cost less to dispose? What system must be established to record and track such material? All of these issues require “accountability.” As another example, ethical codes likely deal with bidding procedures to obtain the best prices from capable suppliers. What controls are needed to monitor the purchasing process, provide for the best prices, and audit the quality of procured goods? All of these issues quickly evolve into internal accounting tasks.

Sustainability — In the years following World War II the economic engines of many companies all over the world began to consume raw materials and produce products at an unprecedented rate in a largely unregulated business environment. The corporate culture involved producing the best product or service at the lowest cost and highest return to the stakeholders involved, primarily the shareholders of the entity. Little regard was often given to the inability to “replace” depleted resources used, or the toll taken on employees or the general population in such endeavors. For example, the quality of air suffered, waterways became polluted, and unknown chemicals were dumped as a by-product of manufacturing processes. In the recent past, the advent of advances in medicine to sustain the population of people has promoted the wide-ranging discussion of sustaining the planet for future generations, including its resources.

Sustainability — In the years following World War II the economic engines of many companies all over the world began to consume raw materials and produce products at an unprecedented rate in a largely unregulated business environment. The corporate culture involved producing the best product or service at the lowest cost and highest return to the stakeholders involved, primarily the shareholders of the entity. Little regard was often given to the inability to “replace” depleted resources used, or the toll taken on employees or the general population in such endeavors. For example, the quality of air suffered, waterways became polluted, and unknown chemicals were dumped as a by-product of manufacturing processes. In the recent past, the advent of advances in medicine to sustain the population of people has promoted the wide-ranging discussion of sustaining the planet for future generations, including its resources.

Most would agree that management has a fiduciary responsibility to shareholders to strategically deploy and manage the assets of the business to generate profit, but not at the expense of the well-being of its people or the environment. Beginning in the early 1980’s the United Nations (UN) engaged in multi-national debates resulting in the creation of the Brundtland Commission whose mission was to unite countries to pursue sustainable development together. The report of the commission identified the interrelated nature of the environment, society, and the economy. Currently most companies consider these three components of sustainable development as a strategic part of the core values and mission of the corporate structure.

Today companies convey progress toward their goals of economic profit along with care for the environment and responsibility to society in a report often called the Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Report or Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Report. Guidelines for reporting have been developed by an international independent standards organization known as the Global Reporting Initiative. These reports can be far ranging, including discussions of reductions in greenhouse gas emissions, water consumption, and the like. Some companies additionally comment on volunteerism efforts, donations, worker safety, and other such matters. While the sustainability reporting guidelines are not mandatory, many large corporate reports are produced after having been audited by independent CPA firms.

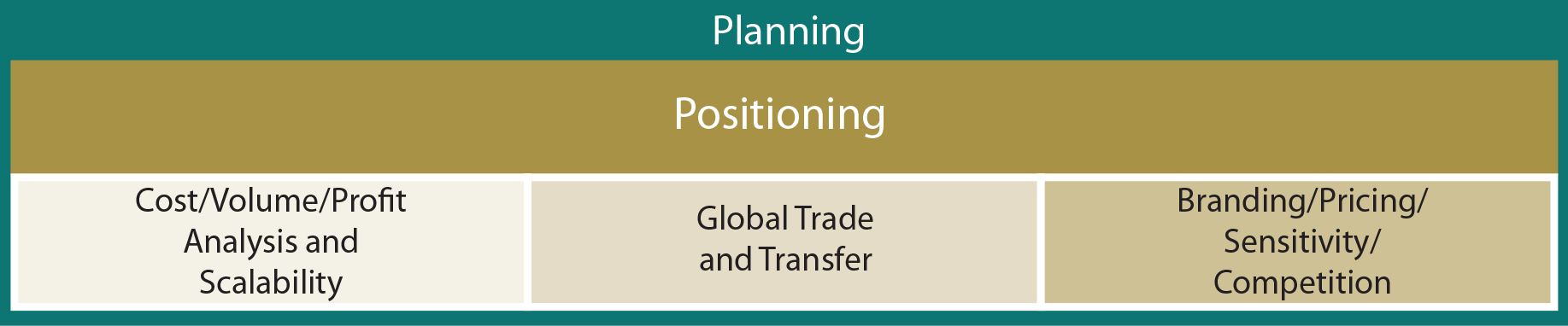

Positioning

An important part of the planning process is positioning the organization to achieve its goals. Positioning is a broad concept and depends on gathering and evaluating accounting information.

Cost/Volume/Profit Analysis and Scalability — A subsequent chapter will cover cost/volume/profit (CVP) analysis. It is imperative for managers to understand the nature of cost behavior and how changes in volume impact profitability. Methods include calculating break-even points and determining how to manage to achieve target income levels. Managerial accountants study business models and the ability (or inability) to bring them to profitability via increases in scale.

Global Trade and Transfer — The management accountant frequently performs significant and complex analysis related to global activities. This requires in-depth research into laws about tariffs, taxes, and shipping. In addition, global enterprises may transfer inventory and services between affiliated units in alternative countries. These transactions must be fairly measured to establish reasonable transfer prices (or potentially run afoul of tax and other rules of various countries involved). Once again, the management accountant is called to the task.

Global Trade and Transfer — The management accountant frequently performs significant and complex analysis related to global activities. This requires in-depth research into laws about tariffs, taxes, and shipping. In addition, global enterprises may transfer inventory and services between affiliated units in alternative countries. These transactions must be fairly measured to establish reasonable transfer prices (or potentially run afoul of tax and other rules of various countries involved). Once again, the management accountant is called to the task.

Branding / Pricing / Sensitivity / Competition — In positioning a company’s products and services, considerable thought must be given to branding and its impact on the business. To build a brand requires considerable investment with an uncertain payback. Frequently, the same product can be “positioned” as an elite brand via a large investment in up-front advertising, or as a basic consumer product that will depend upon low price to drive sales. What is the correct approach? Information is needed to make the decision, and management will likely enlist the internal accounting staff to prepare prospective information based upon alternative scenarios. Likewise, product pricing decisions must be balanced against costs and competitive market conditions. And, sensitivity analysis is needed to determine how sales and costs will respond to changes in market conditions.

Decisions about positioning a company’s products and services are quite complex. The prudent manager will need considerable data to make good decisions. Management accountants will be directly involved in providing such data. They will usually work side-by-side with management in helping correctly interpret and utilize the information. It is worthwhile for a good manager to study the basic principles of managerial accounting in order to better understand how information can be effectively utilized in the decision process.

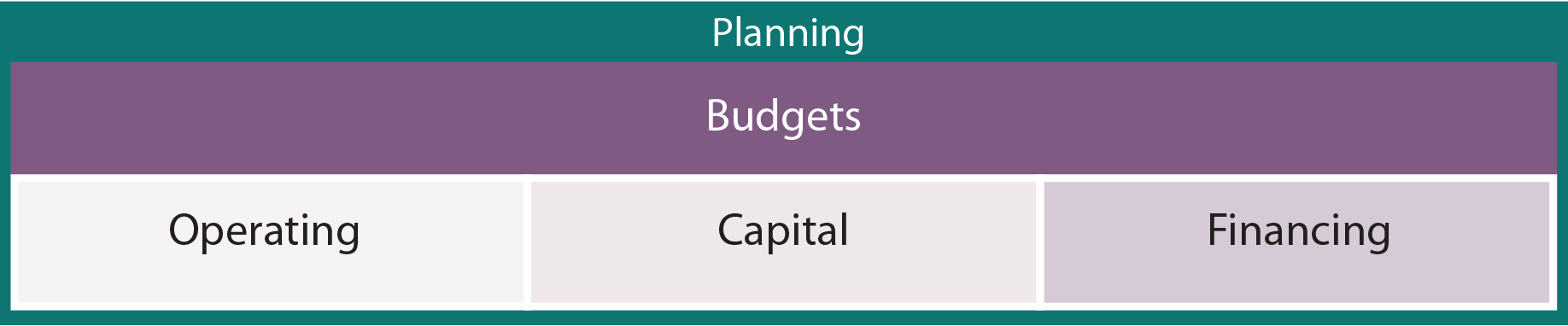

Budgets

A necessary planning component is budgeting. Budgets outline the financial plans for an organization. There are various types of budgets. A company’s budgeting process must take into account ongoing operations, capital expenditure plans, and corporate financing.

Operating Budgets — A plan must provide definition of the anticipated revenues and expenses of an organization, and more. Operating budgets can become fairly detailed. The process usually begins with an assessment of anticipated sales and proceeds to a detailed mapping of specific inventory purchases, staffing plans, and so forth. These budgets oftentimes delineate allowable levels of expenditures for various departments.

Capital Budgets — The budgeting process must also contemplate the need for capital expenditures relating to new facilities and equipment. These longer-term expenditure decisions must be evaluated logically to determine whether an investment can be justified and what rate and duration of payback is likely to occur.

Financing Budgets — A company must assess financing needs, including an evaluation of potential cash shortages. These estimates enable companies to meet with lenders and demonstrate why and when additional financial support may be needed.

The budget process is quite important (no matter how tedious the process may seem) to the viability of an organization. Several of the subsequent chapters are devoted to the nature and elements of sound budgeting.

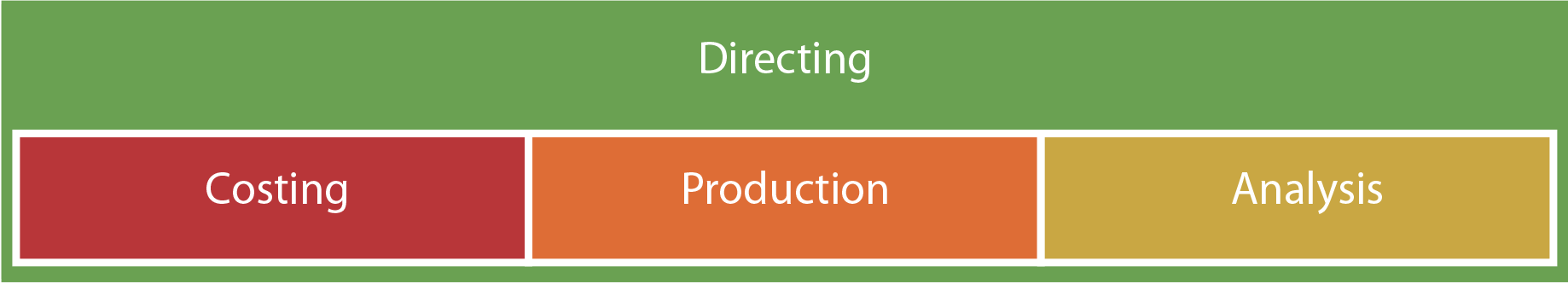

Directing

There are many good plans that are never realized. To realize a plan requires the initiation and direction of numerous actions. Often, these actions must be well coordinated and timed. Resources must be ready, and authorizations need to be in place to enable persons to act according to the plan. By analogy, imagine that a composer has written a beautiful score of music. For it to come to life requires all members of the orchestra, and a conductor who can bring the orchestra into synchronization and harmony. Likewise, the managerial accountant has a major role in moving business plans into action. Information systems must be developed to allow management to maneuver the organization. Management must know that inventory is available when needed, productive resources (people and machinery) are scheduled appropriately, transportation systems will be available to deliver output, and so on. In addition, management must be ready to demonstrate compliance with contracts and regulations. These are complex tasks which cannot occur without strong information resources provided by management accountants.

Managerial accounting supports the “directing” function in many ways. Areas of support include costing, production management, and special analysis.

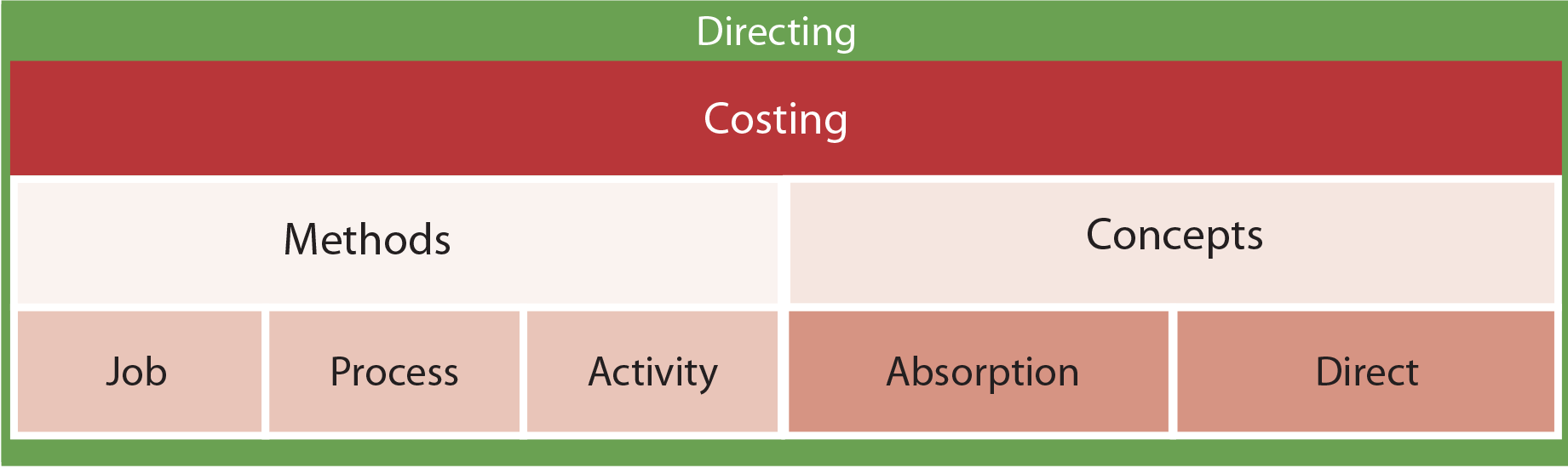

Costing

A strong manager must understand how costs are captured and assigned to goods and services. This is more complex than most people realize. Costing is such an extensive part of the management accounting function that many people refer to management accountants as “cost accountants.” But, cost accounting is only a subset of managerial accounting applications.

Cost accounting can be defined as the collection, assignment, and interpretation of cost. Subsequent chapters introduce alternative costing methods. It is important to know the cost of products and services. The ideal approach to capturing costs is dependent on what is being produced.

Costing Methods — In some settings, costs may be captured by the job costing method. For example, a custom home builder would likely capture costs for each house constructed. The actual labor and material would be tracked and assigned to that specific home (along with some amount of overhead), and the cost of each specific home can be expected to vary.

Some companies produce homogenous products in continuous processes. For example, consider production of paint or bricks used in building a home. How much does each brick or gallon of paint cost? These types of items are produced in continuous processes where costs are pooled together and output is measured in aggregate quantities. It is difficult to identify specific costs for each unit. Yet, it is important to make a cost assignment. For these situations, accountants might utilize process costing methods.

Next, think about the architectural firms that design homes. They engage in many activities that drive costs but do not produce revenues. For example, substantial effort is required to train staff, develop clients, bill and collect, maintain the office, visit job sites, and so forth. The individual architects are probably involved in multiple tasks throughout each day; therefore, it becomes difficult to say exactly how much it costs to develop a specific set of blueprints!

Next, think about the architectural firms that design homes. They engage in many activities that drive costs but do not produce revenues. For example, substantial effort is required to train staff, develop clients, bill and collect, maintain the office, visit job sites, and so forth. The individual architects are probably involved in multiple tasks throughout each day; therefore, it becomes difficult to say exactly how much it costs to develop a specific set of blueprints!

The firm might consider tracing costs and assigning them to activities (e.g., training, client development, etc.). Then, an allocation model can be used to attribute selected activities to a job. Such activity-based costing (ABC) systems are particularly well suited to situations where overhead is high, and/or a variety of products and services are produced.

Costing Concepts — In addition to alternative methods of costing, a good manager will need to understand different theories or concepts about costing. In a general sense, these approaches can be described as “absorption” and “direct” costing concepts. Under the absorption concept, a product or service would be assigned its full cost, including amounts that are not easily identified with a particular item, such as overhead items (sometimes called “burden”). Overhead can include facilities depreciation, utilities, maintenance, and many other similar shared costs.

With absorption costing, this overhead is schematically allocated among all units of output. In other words, output absorbs the full cost of the productive process. Absorption costing is required for external reporting purposes under generally accepted accounting principles. Some managers are aware that sole reliance on absorption costing numbers can lead to bad decisions.

As a result, internal cost accounting processes in some organizations focus on a direct costing approach. With direct costing, a unit of output will be assigned only its direct cost of production (e.g., direct materials, direct labor, and overhead that occurs with each unit produced). Future chapters examine differences between absorption and direct costing.

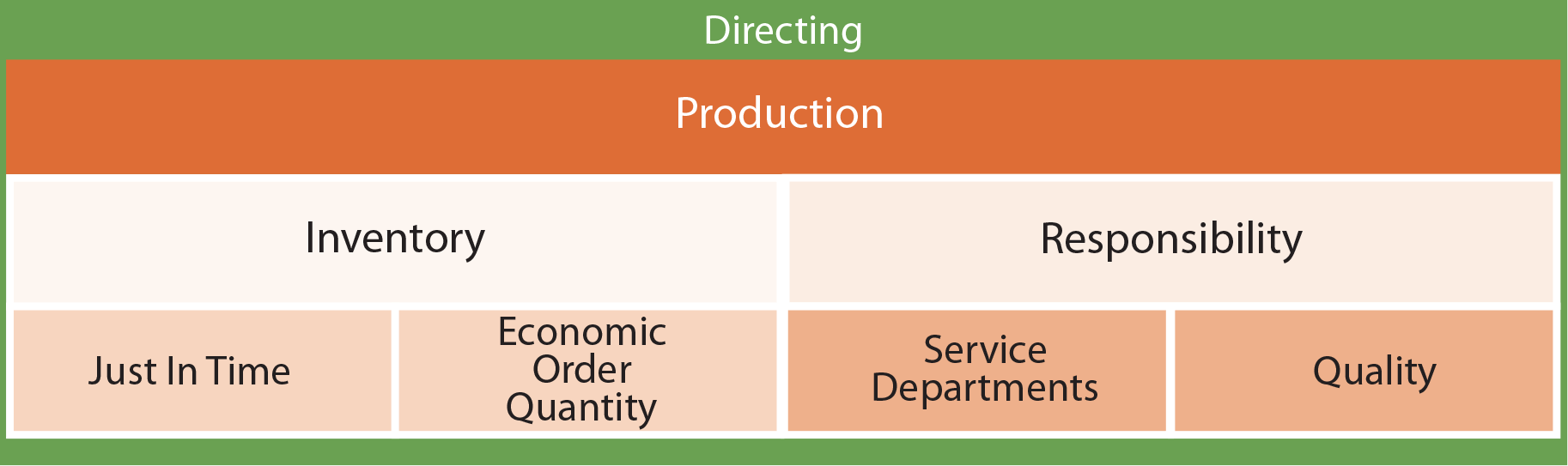

Production

Successfully directing an organization requires prudent management of production. Because this is a hands-on process, and frequently involves dealing with the tangible portions of the business (inventory, fabrication, assembly, etc.), some managers are especially focused on this area of oversight. Managerial accounting provides numerous tools for managers to use in support of production and logistics (moving goods through production to a customer).

To generalize, production management is about running a “lean” business model. This means that costs must be minimized and efficiency maximized, while seeking to achieve enhanced output and quality standards. In the past few decades, advances in technology have greatly contributed to the ability to run a lean business. Product fabrication and assembly have been improved through virtually error-free robotics. Accountability is handled via comprehensive software that tracks an array of data on a real-time basis. These enterprise resource packages (ERP) are extensive in their power to deliver specific query-based information for even the largest organizations.

Business to business (B2B) systems provide data interchange with sufficient power to enable one company’s information system to automatically initiate a product order on its vendor’s information system. Logistics is facilitated by radio frequency identification (RFID) processors embedded in inventory that enable a computer to automatically track the quantity and location of inventory.

Business to business (B2B) systems provide data interchange with sufficient power to enable one company’s information system to automatically initiate a product order on its vendor’s information system. Logistics is facilitated by radio frequency identification (RFID) processors embedded in inventory that enable a computer to automatically track the quantity and location of inventory.

Machine to machine (M2M) enables connected devices to communicate information without requiring human engagement. These developments ultimately enhance organizational efficiency and the living standards of customers who benefit from better and cheaper products. But, despite their robust power, they do not replace human decision making. Managers must pay attention to the information being produced, and be ready to adjust business processes in response. M2M is also becoming known as IOT (internet of things).

Inventory — For a manufacturing company inventory may consist of raw materials, work in process, and finished goods. The raw materials are the components and parts that are to be eventually processed into a final product. Work in process consists of goods that are actually under production. Finished goods are the completed units awaiting sale to customers. Each category will require special consideration and control.

Failure to properly manage any category of inventory can be disastrous. Overstocking raw materials or overproduction of finished goods will increase costs and obsolescence. Conversely, out-of-stock situations for raw materials will silence the production line. Failure to have goods on hand might result in lost sales. Subsequent chapters cover inventory management. Popular techniques include JIT (just-in-time inventory management) and EOQ (economic order quantity).

Responsibility Considerations — Enabling and motivating employees to work at peak performance is an important managerial role. For this to occur, employees must perceive that their productive efficiency and quality of output are fairly measured. A good manager will understand and be able to explain to others how such measures are determined.

Direct productive processes must be supported by many “service departments” (maintenance, engineering, accounting, cafeterias, etc.). These service departments have nothing to sell to outsiders, but are essential components of operation. The costs of service departments must be recovered for a business to survive. It is easy for a production manager to focus solely on the area under direct control and ignore the costs of support tasks. Yet, good management decisions require full consideration of the costs of support services.

Many alternative techniques are used by managerial accountants to allocate responsibility for organizational costs. A good manager will understand the need for such allocations and be able to explain and justify them to employees who may not be fully aware of why profitability is more difficult to achieve than it would seem.

Many alternative techniques are used by managerial accountants to allocate responsibility for organizational costs. A good manager will understand the need for such allocations and be able to explain and justify them to employees who may not be fully aware of why profitability is more difficult to achieve than it would seem.

In addition, techniques must be utilized to capture the cost of quality, or perhaps better said, the cost of a lack of quality. Finished goods that do not function as promised cause substantial warranty costs, including rework, shipping, and scrap. There is also an extreme long-run cost associated with a lack of customer satisfaction.

Understanding concepts of responsibility accounting will also require one to think about attaching inputs and outcomes to those responsible for their ultimate disposition. In other words, a manager must be held accountable, but to do this requires the ability to monitor costs incurred and deliverables produced by defined areas of accountability (centers of responsibility). This does not happen by accident and requires extensive systems development work, as well as training and explanation, on the part of management accountants.

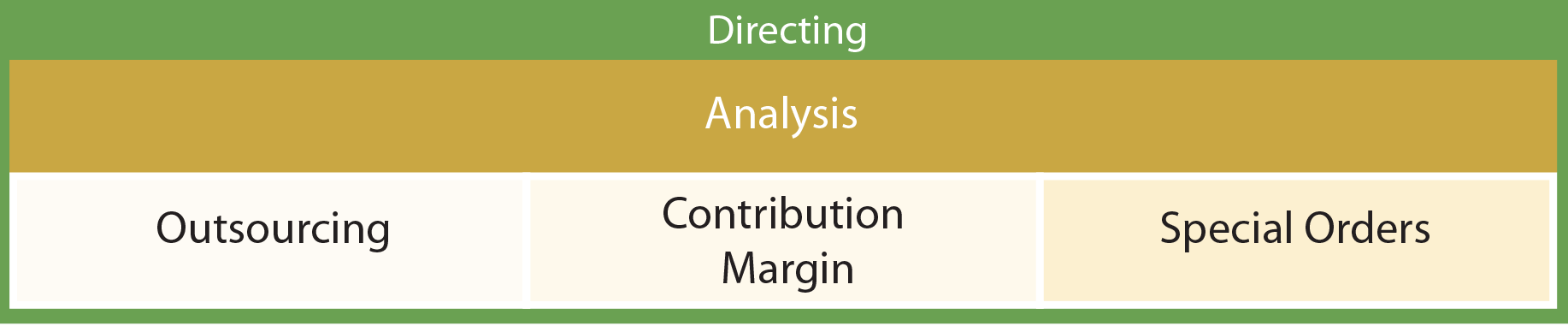

Analysis

Certain business decisions have recurrent themes: whether to outsource production and/or support functions, what level of production and pricing to establish, whether to accept special orders with private label branding or special pricing, and so forth.

Managerial accounting provides theoretical models of calculations that are needed to support these types of decisions. Although such models are not perfect in every case, they certainly are effective in stimulating correct thought. The seemingly obvious answer may not always yield the truly correct or best decision. Therefore, subsequent chapters will provide insight into the logic and methods that need to be employed to manage these types of business decisions.

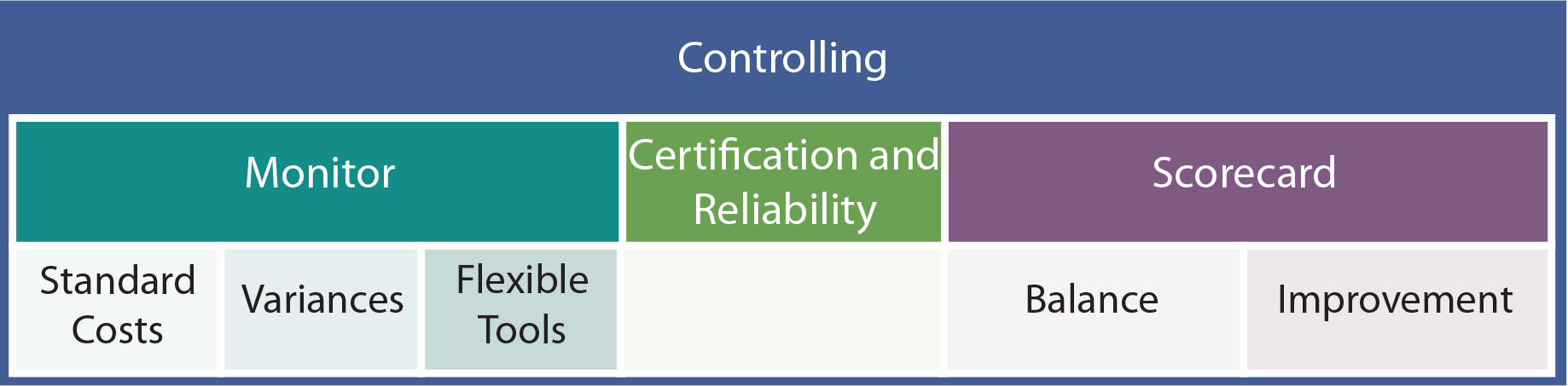

Control

Things rarely go exactly as planned, and management must make a concerted effort to monitor and adjust for deviations. The managerial accountant is a major facilitator of this control process, including exploration of alternative corrective strategies to remedy unfavorable situations.

Things rarely go exactly as planned, and management must make a concerted effort to monitor and adjust for deviations. The managerial accountant is a major facilitator of this control process, including exploration of alternative corrective strategies to remedy unfavorable situations.

In addition, a recent trend is for enhanced internal controls and mandatory certifications by CEOs and CFOs as to the accuracy of financial reports. These certifications carry penalties of perjury, and have gotten the attention of corporate executives. This has led to greatly expanded emphasis on controls of the various internal and external reporting mechanisms.

Most large organizations have a person designated as controller (sometimes termed “comptroller”). The controller is an important and respected position within most larger organizations. The corporate control function is of sufficient complexity that a controller may have hundreds of support personnel to assist with all phases of the management accounting process. As this person’s title suggests, the controller is primarily responsible for the control task; providing leadership for the entire cost and managerial accounting functions.

In contrast, the chief financial officer (CFO) is usually responsible for external reporting, the treasury function, and general cash flow and financing management. In some organizations, one person may serve a dual role as both the CFO and controller. Larger organizations may also have a separate internal audit group that reviews the work of the accounting and treasury units. Because internal auditors are reporting on the effectiveness and integrity of other units within a business organization, they usually report directly to the highest levels of corporate leadership.

Monitor

Begin by thinking about controlling a car (aka “driving”)! Steering, acceleration, and braking are not random; they are careful corrective responses to constant monitoring of many variables like traffic, road conditions, and so forth. Clearly, each action is in response to having monitored conditions and adopted an adjusting response. Likewise, business managers must rely on systematic monitoring tools to maintain awareness of where the business is headed. Managerial accounting provides these monitoring tools and establishes a logical basis for making adjustments to business operations.

Standard Costs — To assist in monitoring productive efficiency and cost control, managerial accountants may develop standards. These standards represent benchmarks against which actual productive activity is compared. Importantly, standards can be developed for labor costs and efficiency, materials cost and utilization, and more general assessments of the overall deployment of facilities and equipment (the overhead).

Variances — Managers will focus on standards, keeping a particularly sharp eye out for significant deviations from the norm. These deviations, or variances, may provide warning signs of situations requiring corrective action by managers. Accountants help managers focus on the exceptions by providing the results of variance analysis. This process of focusing on variances is also known as “management by exception.”

Variances — Managers will focus on standards, keeping a particularly sharp eye out for significant deviations from the norm. These deviations, or variances, may provide warning signs of situations requiring corrective action by managers. Accountants help managers focus on the exceptions by providing the results of variance analysis. This process of focusing on variances is also known as “management by exception.”

Flexible tools — Great care must be taken in monitoring variances. For instance, a business may have a large increase in customer demand. To meet demand, a manager may prudently authorize significant overtime. This overtime may result in higher than expected wage rates and hours. As a result, a variance analysis could result in certain unfavorable variances. However, this added cost was incurred because of higher customer demand and was perhaps a good business decision. Therefore, it would be unfortunate to interpret the variances in a negative light. To compensate for this type of potential misinterpretation of data, management accountants have developed various flexible budgeting and analysis tools. These evaluative tools “flex” or compensate for the operating environment in an attempt to sort out confusing signals. Business managers should become familiar with these more robust flexible tools, and they are covered in depth in subsequent chapters.

Scorecard

The traditional approach to monitoring organizational performance has focused on financial measures and outcomes. Increasingly, companies are realizing that such measures alone are not sufficient. For one thing, such measures report on what has occurred and may not provide timely data to respond aggressively to changing conditions.

In addition, lower-level personnel may be too far removed from an organization’s financial outcomes to care. As a result, many companies have developed more involved scoring systems. These scorecards are custom tailored to each position, and draw focus on evaluating elements that are important to the organization and under the control of an employee holding that position.

For instance, a fast food restaurant would want to evaluate response time, cleanliness, waste, and similar elements for the front-line employees. These are the elements for which the employee would be responsible; presumably, success on these points translates to eventual profitability.

Balance — When controlling via a scorecard approach, the process must be carefully balanced. The goal is to identify and focus on components of performance that can be measured and improved. In addition to financial outcomes, these components can be categorized as relating to business processes, customer development, and organizational betterment.

Balance — When controlling via a scorecard approach, the process must be carefully balanced. The goal is to identify and focus on components of performance that can be measured and improved. In addition to financial outcomes, these components can be categorized as relating to business processes, customer development, and organizational betterment.

Processes relate to items like delivery time, machinery utilization rates, percent of defect free products, and so forth. Customer issues include frequency of repeat customers, results of customer satisfaction surveys, customer referrals, and the like. Betterment pertains to items like employee turnover, hours of advanced training, mentoring, and other similar items.

If these balanced scorecards are carefully developed and implemented, they can be useful in furthering the goals of an organization. Conversely, if the elements being evaluated do not lead to enhanced performance, employees will spend time and energy pursuing tasks that have no linkage to creating value for the business. Care must be taken to design controls and systems that strike an appropriate balance between their costs and resulting benefits. This means that the managerial accountant must also be skilled in helping an organization avoid creating bureaucratic processes that do not lead to enhanced results and profits.

Improvement — TQM is the acronym for total quality management. The goal of TQM is continuous improvement by focusing on customer service and systematic problem solving via teams made up of front-line employees. These teams will benchmark against successful competitors and other businesses. Scientific methodology is used to study what works and does not work, and the best practices are implemented within the organization.

Improvement — TQM is the acronym for total quality management. The goal of TQM is continuous improvement by focusing on customer service and systematic problem solving via teams made up of front-line employees. These teams will benchmark against successful competitors and other businesses. Scientific methodology is used to study what works and does not work, and the best practices are implemented within the organization.

Normally, TQM-based improvements represent incremental steps in shaping organizational improvement. More sweeping change can be implemented by a complete process reengineering. Under this approach, an entire process is mapped and studied with the goal of identifying any steps that are unnecessary or that do not add value. In addition, such comprehensive reevaluations will help to identify bottlenecks that constrain the whole organization.

Under the theory of constraints (TOC), efficiency is improved by seeking out and eliminating constraints within the organization. For example, an airport might find that it has adequate runways, security processing, and luggage handling, but it may not have enough gates. The entire airport could function more effectively with the addition of a few more gates. Likewise, most businesses will have one or more activities that can cause a slowdown in the entire operation. TOC’s goal is to find and eliminate the specific barriers.

Under the theory of constraints (TOC), efficiency is improved by seeking out and eliminating constraints within the organization. For example, an airport might find that it has adequate runways, security processing, and luggage handling, but it may not have enough gates. The entire airport could function more effectively with the addition of a few more gates. Likewise, most businesses will have one or more activities that can cause a slowdown in the entire operation. TOC’s goal is to find and eliminate the specific barriers.

So far, this chapter has provided snippets of how managerial accounting supports organizational planning, directing, and controlling. As one can tell, managerial accounting is surprisingly broad in its scope of involvement. The remaining chapters of this book will examine all of these subjects in detail. First, however, this chapter concludes by introducing key managerial accounting concepts and terminology.

| Did you learn? |

|---|

| Know how business value relates to management decision making. |

| Describe and differentiate between planning, control, and decision-making functions. |

| Be able to explain how strategy, positioning, and budgets are important parts of the planning process. |

| Understand the need for defining the core values of an organization. |

| Be familiar with the CMA and CFM designations issued by the Institute of Management Accountants. |

| Know the basic nature of operating, capital, and financing budgets. |

| Be able to briefly compare and contrast job order, processing, and activity-based costing methods. |

| Distinguish between absorption and direct costing techniques. |

| Be able to describe recent innovations in production management and information systems: ERP, B2B, RFID, M2M. |

| Be familiar with inventory management concepts like JIT and EOQ. |

| Know the basic job duties of a controller and a CFO. |

| What is the purpose of setting standards and monitoring deviations from those standards? |

| What is a balanced scorecard? |

| Discuss the concepts of total quality management and the theory of constraints. |