Some events may eventually give rise to a liability, but the timing and amount is not presently sure. Such uncertain or potential obligations are known as contingent liabilities. There are numerous examples of contingent liabilities. Legal disputes give rise to contingent liabilities, environmental contamination events give rise to contingent liabilities, product warranties give rise to contingent liabilities, and so forth.

Do not confuse these “firm specific” contingent liabilities with general business risks. General business risks include the risk of war, storms, and the like that are presumed to be an unfortunate part of life for which no specific accounting can be made in advance.

Accounting For Contingent Liabilities

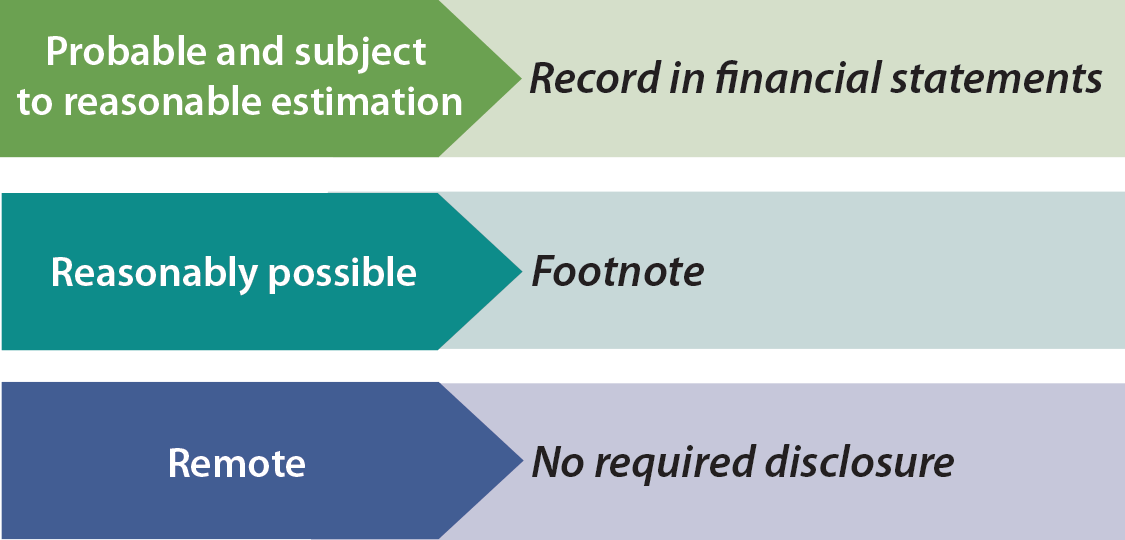

A subjective assessment of the probability of an unfavorable outcome is required to properly account for most contingences. Rules specify that contingent liabilities should be recorded in the accounts when it is probable that the future event will occur and the amount of the liability can be reasonably estimated. This means that a loss would be recorded (debit) and a liability established (credit) in advance of the settlement.

A subjective assessment of the probability of an unfavorable outcome is required to properly account for most contingences. Rules specify that contingent liabilities should be recorded in the accounts when it is probable that the future event will occur and the amount of the liability can be reasonably estimated. This means that a loss would be recorded (debit) and a liability established (credit) in advance of the settlement.

An example might be a hazardous waste spill that will require a large outlay to clean up. It is probable that funds will be spent and the amount can likely be estimated. If the estimated loss can only be defined as a range of outcomes, the U.S. approach generally results in recording the low end of the range. International accounting standards focus on recording a liability at the midpoint of the estimated unfavorable outcomes.

On the other hand, if it is only reasonably possible that the contingent liability will become a real liability, then a note to the financial statements is required. Likewise, a note is required when it is probable a loss has occurred but the amount simply cannot be estimated. Normally, accounting tends to be very conservative (when in doubt, book the liability), but this is not the case for contingent liabilities. Therefore, one should carefully read the notes to the financial statements before investing or loaning money to a company.

There are sometimes significant risks that are simply not in the liability section of the balance sheet. Most recognized contingencies are those meeting the rather strict criteria of “probable” and “reasonably estimable.” One exception occurs for contingencies assumed in a business acquisition. Acquired contingencies are recorded based on an estimate of actual value.

There are sometimes significant risks that are simply not in the liability section of the balance sheet. Most recognized contingencies are those meeting the rather strict criteria of “probable” and “reasonably estimable.” One exception occurs for contingencies assumed in a business acquisition. Acquired contingencies are recorded based on an estimate of actual value.

What about remote risks, like a frivolous lawsuit? Remote risks need not be disclosed; they are viewed as needless clutter. What about business decision risks, like deciding to reduce insurance coverage because of the high cost of the insurance premiums? GAAP is not very clear on this subject; such disclosures are not required, but are not discouraged. What about contingent assets/gains, like a company’s claim against another for patent infringement? Such amounts are almost never recognized before settlement payments are actually received.

Timing Of Events

If a customer was injured by a defective product in Year 1 (assume the company anticipates a large estimated loss from a related claim), but the company did not receive notice of the event until Year 2 (but before issuing Year 1’s financial statements), the event would nevertheless impact Year 1 financial statements. The reason is that the event (“the injury itself”) giving rise to the loss arose in Year 1. Conversely, if the injury occurred in Year 2, Year 1’s financial statements would not be adjusted no matter how bad the financial effect. However, a note to the financial statements may be needed to explain that a material adverse event arising subsequent to year end has occurred.

Warranty Costs

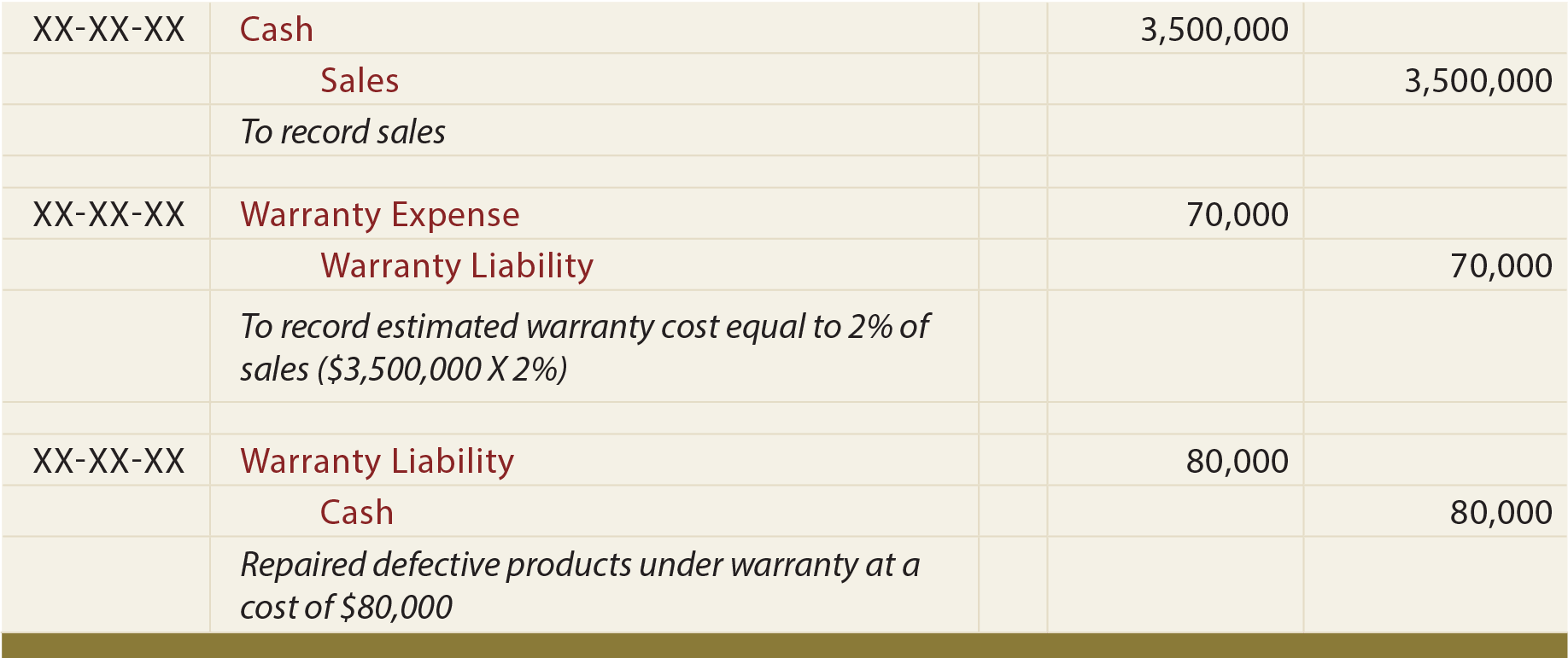

Product warranties are presumed to give rise to a probable liability that can be estimated. When goods are sold, an estimate of the amount of warranty costs to be incurred on the goods should be recorded as expense, with the offsetting credit to a Warranty Liability account. As warranty work is performed, the Warranty Liability is reduced and Cash (or other resources used) is credited. In this manner, the expense is recorded in the same period as the sale (matching principle). Following are illustrative entries for warranties. In reviewing these entries, note the accompanying explanations:

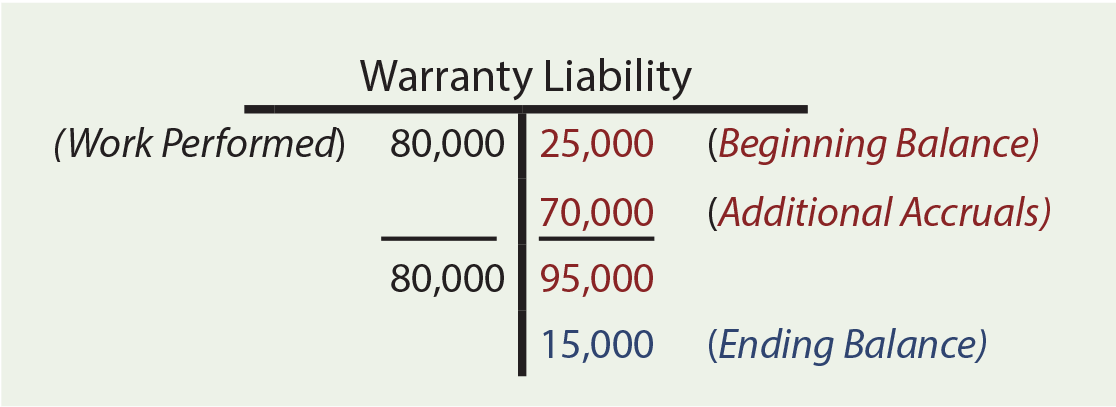

The warranty calculations can require consideration of beginning balances, additional accruals, and warranty work performed. Assume Zeff Company had a beginning-of-year Warranty Liability account balance of $25,000. During the year Zeff sells $3,500,000 worth of goods, eventually expecting to incur warranty costs equal to 2% of sales ($3,500,000 X 2% = $70,000). The 2% rate is an estimate based on the best information available. Such rates vary considerably by company and product. $80,000 was actually spent on warranty work. How much is the end-of-year Warranty Liability? The T-account reveals an ending warranty liability of $15,000.

The warranty calculations can require consideration of beginning balances, additional accruals, and warranty work performed. Assume Zeff Company had a beginning-of-year Warranty Liability account balance of $25,000. During the year Zeff sells $3,500,000 worth of goods, eventually expecting to incur warranty costs equal to 2% of sales ($3,500,000 X 2% = $70,000). The 2% rate is an estimate based on the best information available. Such rates vary considerably by company and product. $80,000 was actually spent on warranty work. How much is the end-of-year Warranty Liability? The T-account reveals an ending warranty liability of $15,000.

Many costs are similar to warranties. Companies may offer coupons, prizes, rebates, air-miles, free hotel stays, free rentals, and similar items associated with sales activity. Each of these gives rise to the need to provide an estimated liability. While the details may vary, the basic procedures and outcomes are similar to those applied to warranties.

| Did you learn? |

|---|

| What is a contingent liability? |

| Describe the criteria that apply in accounting for contingencies. |

| How does timing of events give rise to the recording of contingencies? |

| Be able to account for warranties. |