Sometimes a new car purchase is accompanied by a “trade in” of an old car. This would be a classic exchange transaction. In business, equipment is often exchanged (e.g., an old copy machine for a new one). Sometimes land is exchanged. Exchanges can be motivated by tax rules because neither company may be required to recognize a taxable event on the exchange. The result could be quite different if the asset was sold for cash. Whatever the motivation behind the transaction, the accountant is pressed to measure and report the event.

Commercial Substance

Exchanges that have commercial substance (future cash flows are expected to change) should be accounted for at fair value. Various scenarios are illustrated in the following examples. Recognize that some exchanges may lack commercial substance. For example, two companies may swap inventory and neither expects a significant change in cash flows because of the trade. Gains are not recorded on exchanges lacking commercial substance and are typically illustrated in more advanced courses.

Fair Value Approach

The fair value approach for exchanges having commercial substance will ordinarily result in recognition of a gain or loss because the fair value will typically differ from the recorded book value of a swapped asset. There is deemed to be a culmination of the earnings process when assets are exchanged. In other words, one productive component is liquidated and another is put in its place. The following examples illustrate exchange transactions for scenarios involving both losses and gains.

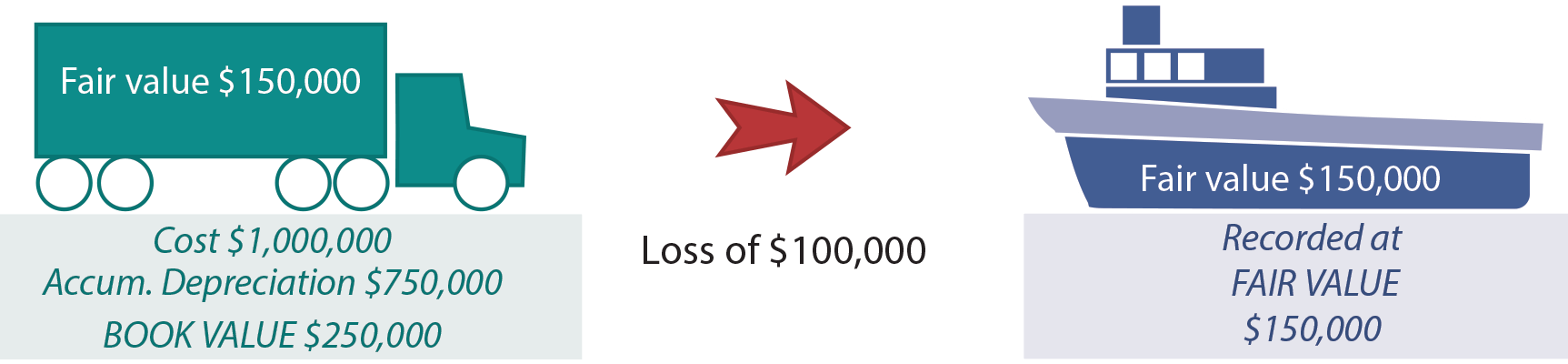

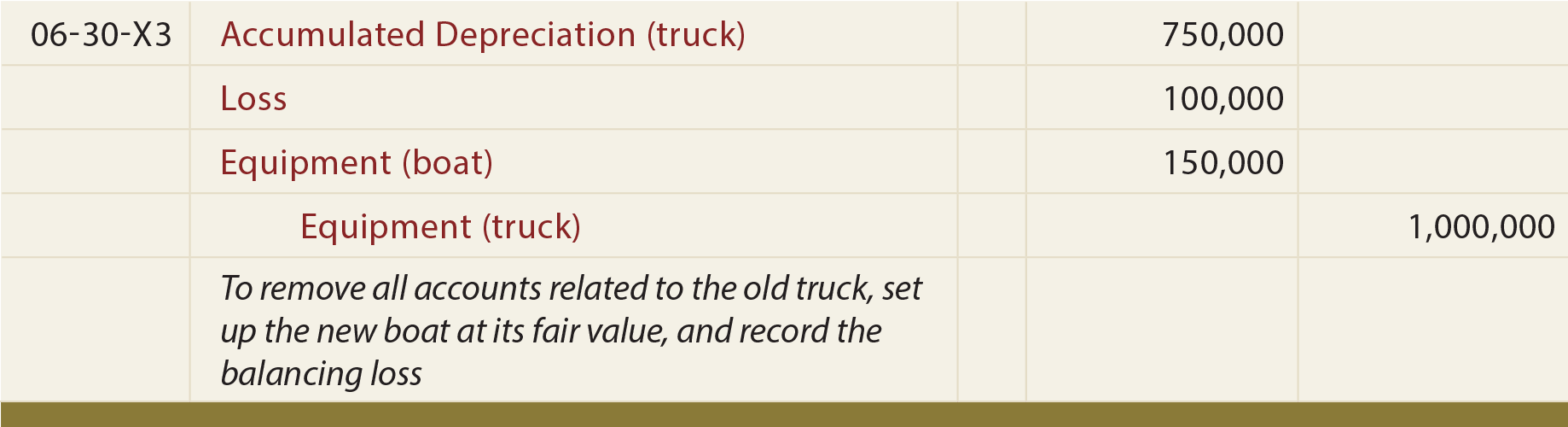

Example A: Loss Implied

Company A gives an old truck ($1,000,000 cost, $750,000 accumulated depreciation) for a boat. The fair value of the old truck is $150,000 (which is also deemed to be the fair value of the boat).

The boat should be recorded at fair value. Because this amount is less than the net book value of the old truck, a loss is recorded for the difference:

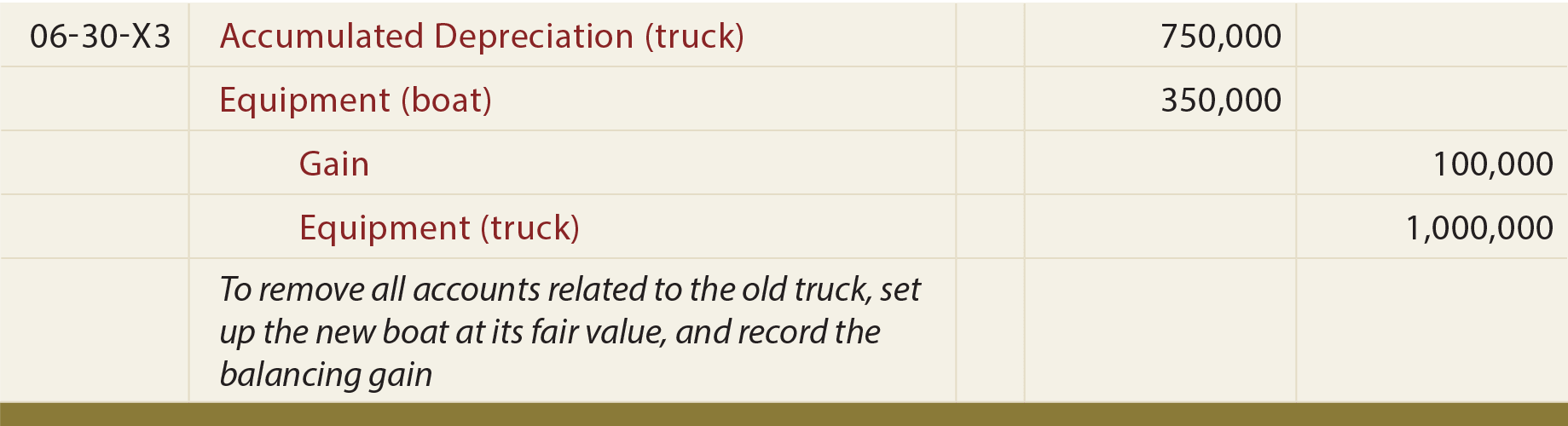

Example B: Gain Implied

Company A gives an old truck ($1,000,000 cost, $750,000 accumulated depreciation) for a boat. The fair value of the old truck is $350,000 (which is also deemed to be the fair value of the boat).

The boat should be recorded at fair value. Because this amount is more than the net book value of the old truck, a gain is recorded for the difference:

Boot

Exchange transactions are oftentimes accompanied by giving or receiving boot. Boot is the term used to describe additional monetary consideration that may accompany an exchange transaction. Its presence only slightly modifies the preceding accounting by adding one more account (typically Cash) to the journal entry.

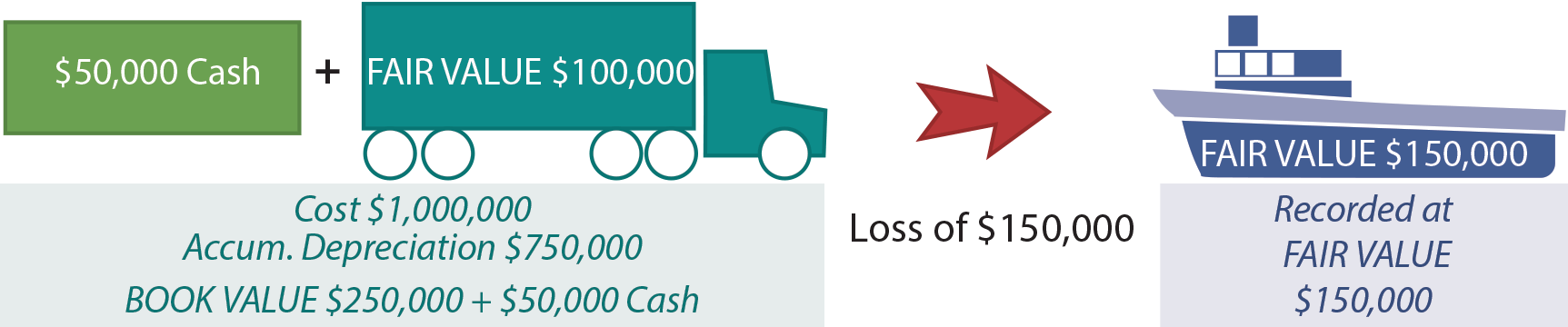

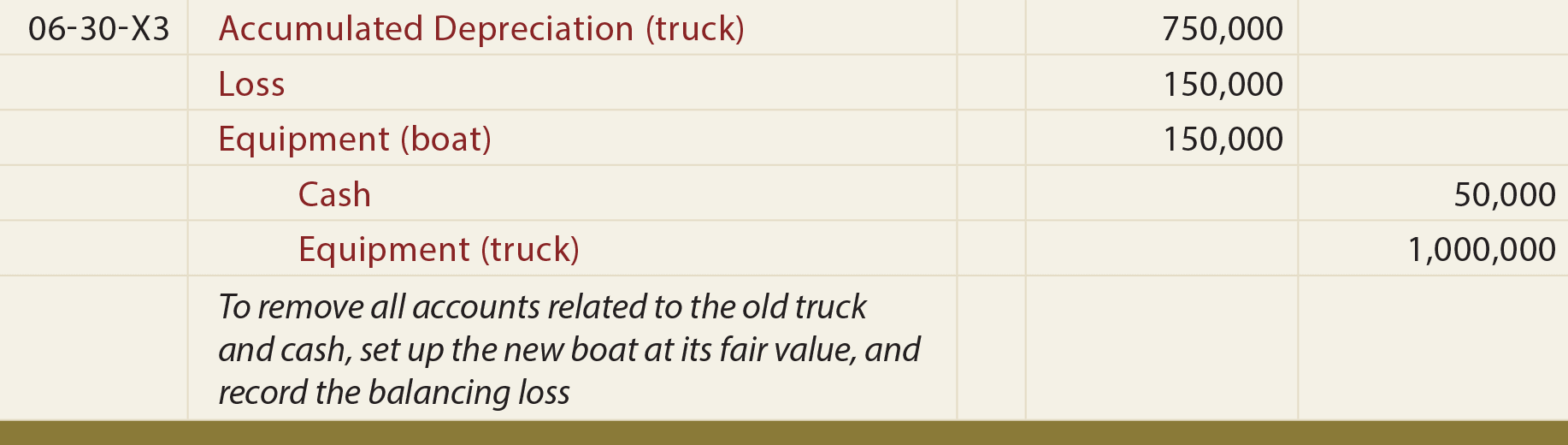

Example C: Boot given

Company A gives an old truck ($1,000,000 cost, $750,000 accumulated depreciation) and $50,000 cash for a boat. The fair value of the old truck is $100,000. The fair value of the boat is $150,000.

Notice that the following entry has an added credit to Cash reflecting the additional consideration. The loss is $150,000. The loss is the balancing amount, and reflects that $300,000 of consideration (cash ($50,000) and an old item of equipment ($1,000,000 – $750,000 = $250,000)) was swapped for an item worth only $150,000. Had boot been received, Cash would have instead been debited (and a smaller loss, or possibly a gain, would be recorded to balance the entry).

| Did you learn? |

|---|

| State the fundamental accounting rules relating to exchanges having commercial substance. |

| Know the general principles for asset exchanges that lack commercial substance. |

| Be able to prepare journal entries necessary to record asset exchange transactions. |

| Understand the meaning and general effect of “boot” in an exchange transaction. |